Being Neurodivergent Means Being Misunderstood Part 1: Why We Are Misunderstood

Being Neurodivergent Means Being Misunderstood 1: Why We Are Misunderstood

Autistic and ADHD people vary a lot, but one thing we have in common is being misunderstood.

This post is the first in a series about these misunderstandings. It will explain what ways we are misperceived and why it happens so often. The second post will focus on a specific reason for misunderstandings: our body language and tone of voice signal different emotions than the ones we actually feel. The third post will explain why we expect to be misunderstood and how we react to it. Finally, the fourth will suggest ways to communicate that create mutual understanding. Kind Theory wants to help you understand your neurodivergent loved ones and make the world kinder and more welcoming to them.

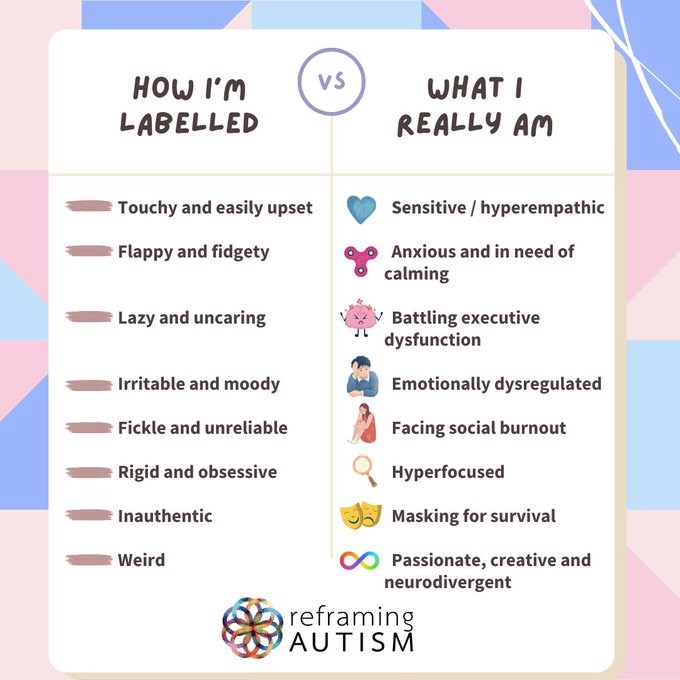

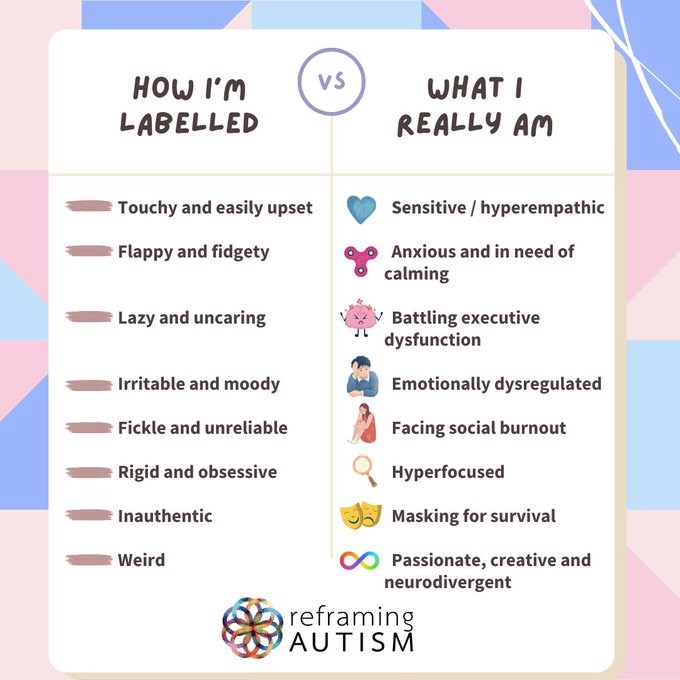

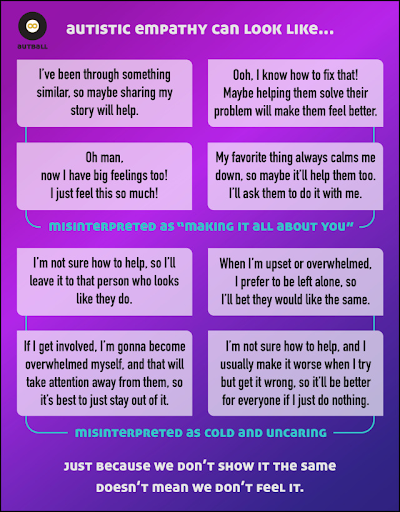

Reframing Autism on Twitter shared examples of how people describe autism versus what autism really is. For example, someone may be perceived as “touchy and easily upset” when they are really “sensitive” and “hyper-empathic.” They may be seen as “flappy and fidgety” when they are “anxious and in need of calming.”

As this list suggests, most misperceptions are negative. Sometimes people assume incorrect motivations, such as “lazy and uncaring.” Other times, as with “weird” or “rude,” they ignore the person’s internal life entirely (which can make neurodivergent people feel like our inner life doesn’t matter to others).

Either way, frequent negative judgments don’t just hurt our feelings. They also weaken our relationships. And, if we start to believe them, they may give us a negative view of ourselves.

There are several reasons why neurodivergent people are often misunderstood.

Misunderstandings Happen Because We Do The Same Things Others Do, But for Different Reasons

Many things neurodivergent people do, neurotypical people do too.

Autistic people stim; neurotypical people fidget.

Autistic people often make limited eye contact; so do neurotypical people sometimes.

People with ADHD forget names, birthdays, and appointments; so do neurotypical people, occasionally.

People with ADHD get distracted and miss what other people are saying; neurotypical people do too, sometimes.

However, neurodivergent people usually do these things for different reasons.

Neurotypical people generally stim when they are bored or anxious, to self-regulate and relieve stress. Autistic people “stim” for a variety of reasons, not only to relieve anxiety and sensory overwhelm. They also stim to express happiness, to ground themselves when understimulated, and because it feels good. Stimming can be a mode of communication as well as a source of regulation for neurodivergent people.

When autistic people look away from someone speaking to them, others assume they’re not paying attention. In fact, they are blocking out distraction from looking at the speaker’s face so as to better understand their words. Research shows that neurotypical people also “look away to think.” They just don’t need to do so as often or as obviously.

Similarly, when autistic people do not make eye contact, they are assumed to be emotionally disconnected, not interested in the other person. In fact, eye contact feels uncomfortably intense to them. [1]

There is a stereotype that people who look away or fidget while talking are lying. (In reality, other possibilities exist: they may be anxious, or just need to think about what they’re saying). Even if these assumptions about body language are accurate for neurotypical people, they are not true for neurodivergent people. As a result, autistic people often face unfair judgments and mistrust:

A number of recent empirical studies have examined how neurotypicals perceive and judge autistics, shedding light on the social barriers faced by autistics in a world built for neurotypicals: Allistic peers are less likely to interact with autistic people because of immediate and unconscious negative judgments that are based purely on social communication style, and not substance. Autistic people are also often perceived by neurotypicals as deceptive or lacking credibility.

Neurodivergent people can interrupt others for a variety of reasons. One reason is poor short term memory. I lose track of my thoughts easily. As a child, I often blurted out ideas before I could forget them, even when other people were already talking. Limited emotional regulation can also contribute. When intense emotions hit, it can be hard to muster the self control to avoid blurting out what I think.

Poor conversational timing can also lead people to interrupt. Gavin Bollard says he can watch a conversation like a tennis match for a long time and find no place to join the conversation. Either he gives up and walks away, or he tries to participate and ends up interrupting. To me, the pauses people make between sentences feel longer than they really are. I think they are done talking when they are merely taking a breath. So, when I start talking, I end up interrupting.

In general, the motivations for interrupting are not the negative ones usually assumed. Instead, the interrupting person is friendly and eager to communicate.

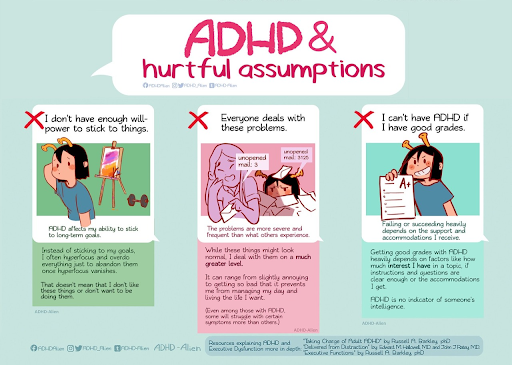

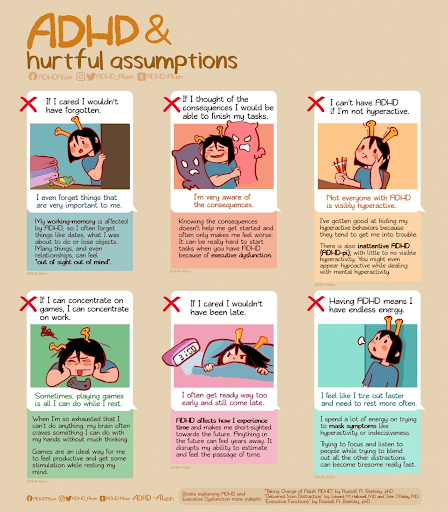

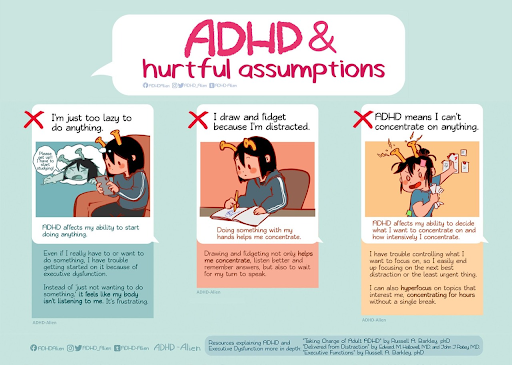

People with ADHD are misunderstood because we do things “everyone” does, but for different reasons. Neurotypical people also forget things and get distracted. But people with ADHD have less control over it. That leads to misunderstandings.

When people with ADHD forget names, appointments, or a loved one’s birthday, others often assume we don’t care. In fact, people with ADHD forget things no matter how much we care and how much effort we make to remember.

Similarly, people often assume that when people with ADHD don’t pay attention to what they say, we don’t care about them or aren’t interested in what they’re saying. In fact, no matter how much we care and want to understand, we may be unable to pay attention.

People with ADHD may struggle to finish projects and produce less than others in the same amount of time. We may be misjudged as being “lazy” and not putting in effort. In fact, we have been desperately struggling to make ourselves do the work. Yet we must overcome difficulties getting started and concentrating, cope with obstacles along the way, remember crucial bits of the task or due dates, multitask, etc. We are working harder than most people to produce less.

ADHD Alien’s series of comics below gives examples of common ways people with ADHD are misjudged.

All these assumptions hurt.

[1] To understand how autistic people can feel when making eye contact, imagine staring into another person’s eyes without blinking for minutes at a time. Most people eventually feel uncomfortable in this situation; autistic people just feel uncomfortable faster. Try it yourself and see.

Misunderstandings Happen Because We React to Things Most People Do Not, in Ways Most People Do Not

Neurodivergent people often experience sensory stimuli (like loud noises, crowded spaces, or perfume smells) as stronger or more unpleasant than other people do. When we avoid or complain about these stimuli, it can be seen as “overreacting.” Neurotypical people can unintentionally gaslight autistic people by saying “it’s not that bad.” To the autistic person, it does feel that bad, and the suffering is quite real.

To function well, neurodivergent people need a consistent routine more than most people do. Thus, they may feel extremely uncomfortable if plans are changed and they don’t know what will happen next. When difficulty “going with the flow” interferes with others’ plans, it can be perceived as selfish, unreasonable, or controlling.

Neurodivergent people are more easily exhausted by social interaction. They may leave social events early or not attend at all. They may then be misperceived as unsociable.

Many autistic people interpret language literally, and miss what is not stated clearly. Especially if they seem intelligent and good with words, they will be assumed to be thoughtless or not listening.

Autistic people can unintentionally violate social norms, sometimes because they don’t know the norms, sometimes because the norms don’t make sense to them. Others assume they are deliberately violating the norms, for the same reasons a neurotypical person would, and therefore must have negative motives.

For example, when neurodivergent people tell the truth very bluntly, they are perceived as being intentionally rude. They may be perceived as impolite and nosy if they ask direct personal questions. In fact, they are trying to express honesty, interest, and engagement with the other person.

It’s reasonable for neurotypical people to be annoyed or frustrated by behavior that they’ve spent their lives learning is rude, or that interferes with their plans. We ask that they not make assumptions about our motivations. Do not let dislike of a behavior become judgment of the person.

Misunderstandings Happen Because We Develop Unevenly and “Out of Order”

Neurodivergent people can have extremely uneven abilities, with huge gaps between our strengths and our weaknesses.

We also develop differently, sometimes learning skills in a different order than most. For example, children who cannot speak sometimes teach themselves how to read. Others may not realize it until the child has access to a reliable means of communication.

A college student might have the academic skills to excel, but lack the ability to keep a consistent eating and sleeping schedule on their own.

Alyssa Hillary describes a person with academic, organizational, and self-advocacy strengths:

She “is preparing for a year abroad in China, where she will be taking advanced Chinese language courses along with one or two direct enrollment courses conducted in Chinese…She generally does well in school, balancing school life with activist life. She has presented at Debilitating Queerness and the Society for Disability Studies, and her work has been featured in a book. She also has an accepted article in an upcoming book.”

This person also has sensory processing and speaking weaknesses, and looks visibly autistic:

“She is sometimes able to speak and sometimes unable to speak, and even when she can speak, typing is often easier. She often carries a blanket with satin binding with which to stim. While she is usually able to look at people, she does not make eye contact. She is hypersensitive to many kinds of sound, and does not tolerate flashing lights. When upset or overloaded, she has been known to chew on her hands.”

(To give away the punchline: Both are descriptions of Alyssa).

Another example of extremely uneven skills: When she was a college student, Zoe Gross wrote about being stuck in her room, unable to leave and go to class. She needed help from a friend and a flowchart to leave her dorm room.

Unfortunately, because few people develop this way, neurodivergent people may be disbelieved about their abilities. Neurodivergent people who are intellectually gifted – with IQ in the top 2-5% of the population – have especially uneven abilities and are constantly misunderstood. Their families, neighbors, teachers, neighbors, and peers may have never met someone with such uneven skills. They may not even know such development is possible.

The myth that intelligence means being good at everything increases misunderstandings.

Open Doors Therapy explains:

This uneven behavioral and cognitive profile can confuse people. Why? Well, people often expect that a bright and gifted person is exceptional across the board. The expectation is that they would be good at everything. Thus, a neurotypical person may be confused by a person on the autism spectrum who is great at certain things but struggles in others. Employers may be dumbfounded. Unfortunately, this is what often happens when incorrect assumptions are made about a person with autism.

I often hear neurodiverse teens and young adults being referred to as lazy, resistant, rude, or oppositional. However, I find that these are often misinterpretations. For instance, sometimes what appears to be laziness in a neurodiverse teen or adult is really fear and avoidance of certain situations. They may be avoiding situations that require skills they feel like they do not possess. For example, they may not want to go to party because they find it difficult to read social cues and track a group conversation. Situations, [sic] where they lack skills trigger high levels of anxiety for them. Also, they may already be feeling low self-esteem and low confidence in their abilities. They might not have the coping skills or emotional regulation skills to handle uncomfortable feelings.

How a person is misunderstood depends on whether their strengths or their weaknesses are visible. People tend to see one or the other, but not both.

Generally, a person who speaks well and performs at least average academically may be viewed as “high functioning”: capable across the board, and not needing much help. By contrast, someone with no or limited speech, who is very behind academically, may be viewed as “low functioning”: incapable in all areas, and needing help with everything.

Whether a person is judged to be “high functioning” or “low functioning,” the outcome is bad. As Alyssa Hillary puts it:

“High functioning means your needs get ignored. Low functioning means your abilities get ignored.”

Misunderstandings Happen Because We Function Inconsistently

The hallmark of neurodivergence, especially ADHD, is inconsistency. What we are able to do changes from day to day and moment to moment. Susan Lasky explains:

“It’s difficult for others to understand how a person with ADHD (child or adult) is able to do something sometimes, even excel at it, and then be unable to perform at an ‘acceptable’ level the next day, or even the next hour…There are days when a person with ADHD can be exceptionally productive, and others where they’ll spend most of their time in a fog. Sometimes there’s a reason (and when you know what it is there may be compensatory strategies that will help jump start action – that’s the goal of coaching!), but mostly there’s no clear reason.”

In fact, an area of psychology and neuroscience research supports the idea that the most consistent symptom of ADHD is not hyperactivity or difficulty paying attention, but inconsistency (which researchers call “intra-individual variability” or “response variability”).

All people have more difficulty doing things well when they are stressed, tired, or overwhelmed. These and other factors reduce neurodivergent people’s abilities even more than other people’s.

We may not even know all the factors that affect us. Nor do we get useful information from others, especially if we are diagnosed late or not at all.

The fact that we can do the same task one day but not the next confuses others, and often ourselves. It doesn’t help when we can’t explain our unevenness.

Others misunderstand our fluctuations in ability as due to changes in our motivation and in how much effort we choose to make:

“People think you don’t care, or you would be able to do ‘it,’ whatever ‘it’ is. They take your lack of performance, or interest, personally.” – Susan Lasky

Others appear unaware that we are at least as confused and frustrated as they are. Not being able to do things we know we “can” do – or even predict when we’ll be able to do them – makes us feel helpless. It’s demoralizing.

Misunderstandings Happen Because Of Stereotypes About Our Diagnoses

People who know our diagnoses often make assumptions about us based on what they think autism and ADHD are like. Unfortunately, news and fictional media are filled with stereotypes about autism and ADHD. Some of these are inaccurate in general. Others apply to autistic or ADHD people as a group, but not to every person in all situations.

An autistic person explains how invisible you feel when people assume you are completely different than you really are:

“There’s something very stifling about knowing that 99% of the population’s idea of who you are and what your life is like bears little to know [sic] resemblance to, well, who you are or what your life is like.

Things like hearing people ask damning questions about whether or not people like you are capable of love or empathy or self-awareness, without ever actually asking anyone like you for confirmation.

Knowing, wherever you are, that there’s a good chance that many people in the immediate area believe that autistic people can’t/don’t do whatever you’re currently doing.

Seeing people claim that certain fiction books give a ‘good insight into the mind of someone with autism/Aspergers’, when these books in fact contained 2D, exaggerated stereotypes of people like you, written by poorly-informed non-autistic people. Being completely unable to find a book containing a realistic portrayal of someone like you, because that wouldn’t sell.

It makes you feel completely erased from the world.”

The world is full of inaccurate, exaggerated stereotypes of autism and ADHD. The existence of a much-hyped “Autism Awareness Month” every April does little to help, and arguably exacerbates the problem. Here are some sources of stereotypes:

- Fictional characters with the “autism” label, especially ones written by neurotypical people, are often jumbles of DSM traits without a coherent internal life, reasons for their behavior, or a history. Neurotypical reviewers, unaware of this, praise these books for providing insight into “the autistic mind.” These glowing reviews further fool unsuspecting readers who want to better understand their loved ones. Unfortunately, such characters as Rain Man[2], Sheldon Cooper from Big Bang Theory, and Christopher from The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime stick in people’s minds.

- Fear-Mongering: Groups with an axe to grind point to increasing rates of autism and ADHD diagnoses as a “public health crisis” caused by whatever they fear, from vaccines to power lines to toxic chemicals. Those concerned about violence such as mass shootings sometimes scapegoat autistic or mentally ill people.

- Autism Charities: The largest, most visible autism-related charities present autistic people as children, as extremely disabled, and as burdens on the world who make others miserable.

- The Limits of “Expert” Knowledge: In the mid-twentieth century, psychoanalysis was accepted as gospel. The field created stereotypes of autistic people as cut off from others and unable to communicate. Later, evolutionary and cognitive psychologists interested in how humans develop a “theory of mind” developed specific laboratory tasks for measuring it. In the 1990s, these tasks inspired faulty theories: autism was supposedly “mind blindness” caused by an “extreme male brain.” Meanwhile, over decades, the definitions of autism and ADHD broadened, so that ever more people qualified, with ever better ability to speak for themselves. Increasing numbers of them began talking about their experiences, providing counterevidence to “experts’” theories about autism and ADHD. Researchers’ opinions often lag behind neurodivergent people’s thinking. Yet, researchers are taken more seriously and have more opportunities to be heard, so their misunderstandings persist.

Stereotypes lead people to expect negative things that aren’t true. People may assume without evidence that a particular autistic person will not make a good friend, romantic partner, parent, or coworker.

Stereotypes can also lead people to ignore what really is there. Parents who are taught that their children can’t care about their feelings ignore their children’s attempts to comfort them. People who are taught to see “monologuing” about passionate interests as a “behavior” to discourage will miss the speaker’s eagerness to share what they love.

[2] Fun fact: Did you know that the main inspiration for the autistic character in Rain Man, Kim Peek, wasn’t actually autistic?

In short

Being neurodivergent often means a lifetime of being judged more negatively than we deserve.

We are misunderstood for the following reasons:

- We do the same things other people do, but for different reasons.

- We do things other people generally do not do.

- Our abilities are uneven and inconsistent.

- Inaccurate stereotypes about us are everywhere.

My next post will explain one especially confusing reason it happens: neurodivergent people’s facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice seem to signal different emotions than we really feel.

Further Reading

Being Misunderstood

Being Misunderstood by Lynne Soraya

Eight Things Autistic People Do That You’re Misreading as a Neurotypical by Jaime A. Heidel

ADHD Symptoms in Adults Aren’t Character Flaws by Black Girl, Lost Keys has a long, excellent list of assumptions people make about those with ADHD. Scroll down for it.

Answer to the question on Quora, “What do most people misunderstand about ADHD?”, by Susan Lasky

Examples of misunderstandings with husband and coworkers based on gesture: Adventures in Cross Cultural Communication by Lynne Soraya

Conversations with People with ASDs can Leave You with the Wrong Impression by Gavin Bollard

“Homonyms” in Aspergers Behavior, Part 1 by Enniene Ashbrook

They Thought I was Lazy When I was Just Autistic by Laina Eartharcher

Autistic Ways of Reacting by Ischemgeek

Uneven Skills

Meet Two People by Alyssa Hillary

On Functioning Labels by Ischemgeek

Unevenness and Inexplicability by Amanda Forest Vivian

Emily Morson

About the Author

Emily M. is a writer fascinated by the infinite variety of human minds. She grew up inexplicably different and was diagnosed as an adult with several forms of neurodivergence, including ADHD and an auditory discrimination disability. Feeling as if she were living life without a user's manual, she set out to create her own. In the process, she met other neurodivergent people on similar quests. She began working with them, advocating for inclusion, accessibility, and autism acceptance. Seeking to understand how neurodiverse minds work, she became a cognitive neuroscience researcher.

Her favorite research topic: what do children learn from their intense, passionate interests? Wanting to help neurodivergent people more directly, she trained as a speech/language therapist. Ultimately, she turned to writing, combining research with personal experience to explain autism and ADHD and champion acceptance – because everyone is happier when they are seen and accepted for who they are. She envisions a world where neurodiverse people have equal opportunities for education, loving relationships, and meaningful work.

She also blogs about autism and ADHD research at Mosaic of Minds. You can chat with her on Twitter: @mosaicofminds