Being Misunderstood 3: We Expect to be Misunderstood

Being Misunderstood 3: We Expect to be Misunderstood

Neurodivergent People Expect to be Misunderstood…and That Only Makes Things Worse

From early childhood on, neurodivergent people are often misunderstood. My previous two posts in this series explain why it happens so often.

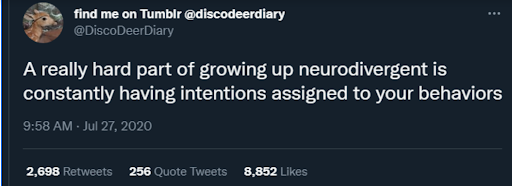

The problem is not just that we are misunderstood, but that the misjudgments are always negative.

DiscoDeerDiary continues,

“Like if you never learned [arbitrary ‘friendly’ social convention] then you’re ‘trying to be rude’ or if you find yourself unable to do [task that neurotypicals consider easy] then you’re ‘not trying hard enough’ or ‘don’t really care’ or if you want to be alone because you’ve gotten overwhelmed by a conflict you’re ‘giving the silent treatment’ and ‘being passive aggressive.’

The best part is that if you deny any of these, the neurotypicals will tell you you’re lying to protect your ego [sic]”.

Liz Bernstein adds, “The number of times I was called ‘manipulative’ and ‘self-centered’…it baffled me.”

Gabe Netz agrees:

“So many times when I would try to explain that I was thinking/feeling X and was told “No, I can tell by [insert non-verbal cue I don’t have control over] that you’re REALLY thinking/feeling Y” and had to actually argue my own feelings and not be believed.”

In the short term, being misjudged and disbelieved hurts. It’s especially painful if we are then told that the other person knows our feelings better than we do ourselves, or if we’re rejected.

It’s never easy to feel that you tried to connect with someone only to then be rebuffed and judged. – Lynne Soraya

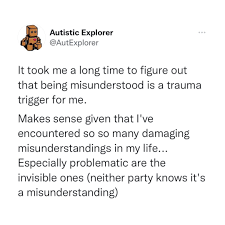

In the long term, as a pattern of this treatment builds up, it can become traumatic.

Like most people, neurodivergent folks notice patterns in life and learn from them. We come to anticipate that other people will misjudge us, and look for ways to prevent it.

Twitter user “alien dreams” (@aliendreams4) explains, “a giant chunk of our communication style may be adaptive to every question we’re asked being some kind of a weird Gotcha, having to always back up what we say, being disbelieved, or coming to a conclusion that the other person can’t wrap their mind around at all.”

Unfortunately, it can be hard for neurodivergent people to understand why these misunderstandings happen | and what we need to explain.

How We React to Being Misunderstood

We often don’t understand why we are being misjudged.

As explained in the previous post in this series, sometimes we are unaware of what behavior others misunderstood.

Other times, those judging us do not state what behavior caused the misunderstanding in specific enough terms for us to understand. That is, instead of saying “you didn’t say hi to me when I came in,” they say something vague, like “you were rude.” The more literally we understand language, the more often this happens.

If we’re really unlucky, the person judging us won’t give an explanation at all.

Thus, neurodivergent people live in a world where at any given moment, someone could judge our motives or character negatively, for unknown reasons. It’s hard to feel safe in a situation like that.

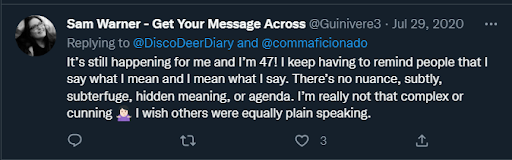

So, we try to explain ourselves before any misunderstandings can happen.

“I spend all my life trying to find someone who will understand, but because of my life, I wind up having to give them a tutorial about how I act and why.” – Lynne Soraya

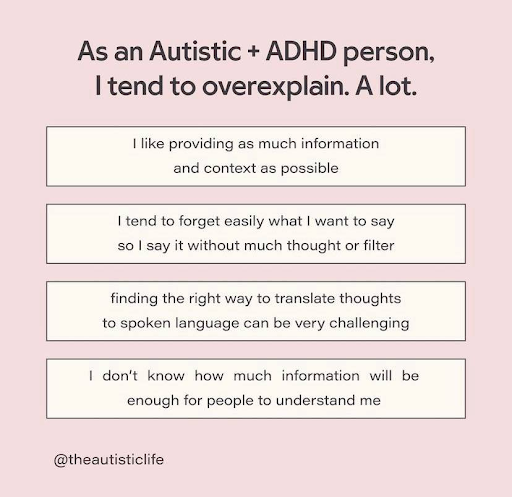

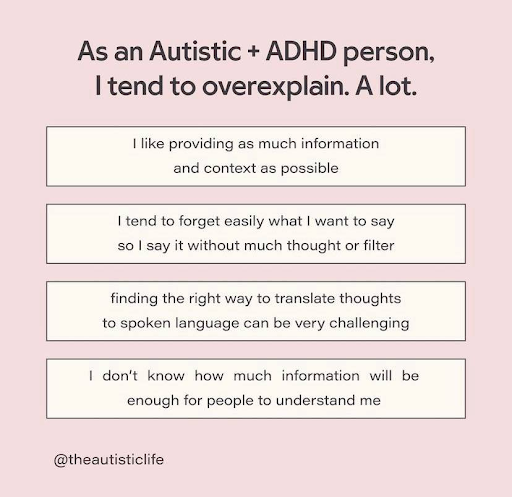

Neurodivergent people often overexplain everything we do, including things that wouldn’t upset anyone, because we don’t know what seemingly innocuous thing might give offense.

We explain our motivations constantly without being asked, because we don’t know when someone will need an explanation.

We give too many details, because we don’t know what will cause a misunderstanding. But, if we throw out enough possibilities, surely one of them will stick. Better to be safe

The executive function difficulties that come with ADHD and autism only compound the problem. We have difficulty deciding what to say and what to leave out. Not only do we say too much, but it takes extra time to figure out what to say.

Other Forms of Anticipatory Rejection

Mette Harrison uses the word “anticipatory rejection” to talk about how she behaves towards people when she constantly expects to be judged and rejected.

For example, she makes fun of herself for anything she might be judged for, before anyone else can do so:

“If I said the reasons that I was going to be rejected up front and everyone laughed and agreed, then somehow it was less painful than being surprised (autists also hate being surprised) by rejection later. It might also have been a strange way for me to try to figure out what the reasons were for my social rejection and try to deal with them, though I was never great at this.”

Mette may even avoid approaching people at all, if the risk of rejection seems too high:

“It comes out, as well, in me judging people as “too popular” in advance and not making friends with anyone who appears (by my very limited understanding) to be above me in the social hierarchy because that would be a waste of time and energy for me.”

This post probably just scratches the surface of the many ways neurodivergent people act when we expect to be misjudged.

If you are neurodivergent, which ones have I missed?

If you are neurotypical, reflect on what you’ve noticed, and consider discussing the topic with neurodivergent loved ones if they’re comfortable with that.

Our Attempts to Be Understood Usually Backfire

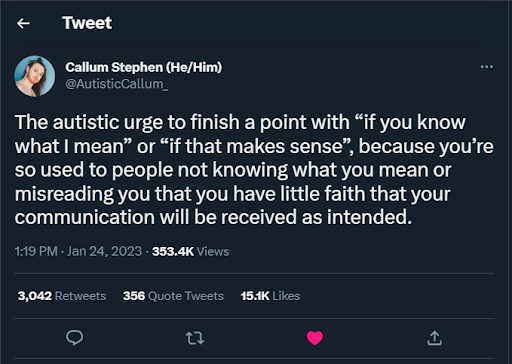

Ironically, people don’t understand our attempts to avoid being misunderstood – because just making such attempts is atypical. Most people don’t go through life expecting to be misunderstood and trying to guard against it.

At best, listeners may find long, unasked-for explanations annoying. At worst, we can be misperceived as “making excuses.”

All of this sounds bleak, so let me share a positive idea. For me, a lifetime of being misunderstood left me driven to express my thoughts and feelings through clear thinking and writing. This painful experience has probably developed my greatest passion and skill.

(I don’t recommend the experience to other writers).

Am I misjudging the neurodivergent people in my life? What can I do about it?

If you are feeling uncomfortable, wondering if you’ve been misjudging the neurodivergent people in your life, I’m sorry to say you probably have [1]. Don’t worry, it’s inevitable to some extent. People whose brains work differently will necessarily misunderstand each other at some point.

It’s like communicating with people from another culture, or of different age or sex or socioeconomic status.

When people communicate their emotions differently and have different assumptions about how the world works, they will misunderstand each other.

Miscommunications with people of different cultures, age, sex, or socioeconomic status aren’t always traumatic, however. That’s because we approach such interactions with the benefit of the doubt. We know that misunderstandings can happen, and make an effort to avoid and move past them, not assign blame to the other person.

Unfortunately, we do not treat neurodivergent people so kindly.

It is not necessarily damaging to misunderstand another person. What hurts people is when misperceptions are always negative, and do not get revised.

The damage happens when people dig into their own assumptions, refuse to ask neurodivergent people about our perspective, or disbelieve what we say.

We need to approach neurodivergent people with the benefit of the doubt, as if they came from another culture.

In the next and final post of this series, I will explain how to use this perspective to understand and communicate with neurodivergent people in our lives.

[1] By the way, being neurodivergent yourself doesn’t prevent you from misjudging your loved ones in this way. Sometimes neurodivergent (though undiagnosed) family members have ascribed to me negative motives I don’t have. In explanation, they quote my words back at me, saying, “but what else can that mean?”

Further Reading:

A twitter thread where neurodivergent people talk about having people incorrectly assume they have negative intentions.

Eight Things Autistic People Do That You’re Misreading as a Neurotypical by Jaime Heidel

Has ADHD Warped Your Sense of Self? It’s Time to Reclaim Your Story — and Power by Alise Connor

Autistic Body Language by Emma

Neurotypicals, Listen to Our Words, Not Our Tone by Ira Kraemer

Anticipatory Rejection and Autists by Mette Harrison

Sensory Sensitivity and Problem Behavior by Lynne Soraya

Emily Morson

About the Author

Emily M. is a writer fascinated by the infinite variety of human minds. She grew up inexplicably different and was diagnosed as an adult with several forms of neurodivergence, including ADHD and an auditory discrimination disability. Feeling as if she were living life without a user's manual, she set out to create her own. In the process, she met other neurodivergent people on similar quests. She began working with them, advocating for inclusion, accessibility, and autism acceptance. Seeking to understand how neurodiverse minds work, she became a cognitive neuroscience researcher.

Her favorite research topic: what do children learn from their intense, passionate interests? Wanting to help neurodivergent people more directly, she trained as a speech/language therapist. Ultimately, she turned to writing, combining research with personal experience to explain autism and ADHD and champion acceptance – because everyone is happier when they are seen and accepted for who they are. She envisions a world where neurodiverse people have equal opportunities for education, loving relationships, and meaningful work.

She also blogs about autism and ADHD research at Mosaic of Minds. You can chat with her on Twitter: @mosaicofminds