Being Neurodivergent Means Being Misunderstood 2: Why Neurodivergent People’s Behavior Doesn’t Always Match Our Feelings

Being Neurodivergent Means Being Misunderstood 2: Why Neurodivergent People’s Behavior Doesn’t Always Match Our Feelings

Neurodivergent people often do not know why we are misunderstood and what we need to explain.

Sometimes, that happens because neurotypicals are reacting to behavior that is invisible to the neurodivergent person.

Our facial expressions, body language, and tone of voice don’t always match the way we feel inside. However, we do not realize it. Thus, a mismatch happens where we only know how we feel, and others only know how we are behaving. Everyone involved ends up confused and frustrated.

Why Doesn’t Our Behavior Match Our Stated Feelings?

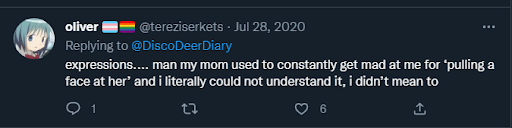

Often, we do not realize our nonverbal behavior doesn’t match the way we feel inside. We cannot sense our facial expressions, postures, and tone of voice that others are perceiving, so we are unaware of them.

We know how we feel and that we are expressing our emotions. So, as far as we know, we are producing the expected signals for our feelings.

For me, it took a while to learn. I had to find out by making sense of comments from friends and family about behavior I could not sense and did not know existed.

Misunderstandings are Mutual

Not surprisingly, both the mismatch between our expressions and our feelings, and our unawareness of it, can cause misunderstandings.

Neurotypical people use the only clues available to them – our behavior – and conclude we must be feeling emotions we don’t actually feel. Then they react accordingly.

Their reactions don’t make sense to us. They are not appropriate in the context of the emotions we feel, and think we are expressing. Neurotypical people’s reactions often seem irrational, unfair, or mean.

Some people say they’re so confused by neurotypical people’s behavior that they don’t learn why body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice matter in the first place. Jaime A. Heidel says:

“When an NT person interrupts an attempt at a critical piece of ND communication to bring up tone of voice, it feels, to us, like we’ve come to you bleeding out, but you ignore that because you’ve noticed we have a strand of hair out of place, and that MUST be addressed first before the medical emergency is even considered.”

Two Ways Our Emotions and Behavior Mismatch

There are two ways our emotions can be misread. First, it can look as if we feel one emotion when we are really experiencing another. In particular, we may not know that we sound angry when we are actually stressed or anxious. My family and I do this a lot.

Facial expressions can also cause confusion. People have asked me why I am rolling my eyes or making a “strange” facial expression I don’t feel myself making.

Second, autistic people may feel an emotion and not appear to be expressing one at all. Their face may look blank when they are happy, or just thinking hard. Smiling to express happiness is automatic for neurotypical people in many cultures, but it may take energy and deliberate choice for an autistic person.

Autistic people also may not appear to express their emotions in body language or gestures. Body language that is automatic for neurotypical people might require energy and motor coordination for an autistic person. (Motor coordination is often a disability for autistic people and ADHD’ers). Autistic people who can understand typical facial expressions and body language won’t necessarily produce those signals themselves.

Whether they see the wrong emotion or none at all, neurotypical people don’t detect the signals they associate with our real emotions, so they misunderstand what we feel.

Why does what we express differ from what we feel? Why don’t we know it? Here are some possibilities.

Different Automatic Ways of Expressing Emotions

We might be wired to nonverbally express emotions differently than neurotypical people do.

Many people think the way humans express emotions is straightforward. For example, when people are genuinely happy, they smile in a specific way that includes the eyes. When people are excited, their pitch goes up and they talk louder and faster. When people are angry, they speak more loudly and emphatically and they gesture more forcefully.

There’s even a theory that all humans in all cultures evolved to express several basic emotions the same way.

However, there is still plenty of room for neurodivergent people to vary.

First, humans feel more than the four to seven basic emotions researchers identified. Many emotions involve social or cultural content – for example, guilt, pride, shame, anticipation, nostalgia, and homesickness. There are even emotions identified and named by some cultures and not by others, such as the Norwegian “forelsket,” that ecstatic, obsessive feeling at the very beginning of a relationship, or Spanish “duende,” the feeling of being moved by art. On top of that, cultures differ in their “display rules”: who can express which emotions, when, with what intensity.

If cultures can express emotions differently, why not neurotypes?

Neurodivergent people might simply be wired with their emotions attached to different patterns of facial expressions and tone of voice than neurotypicals have.

For example, autistic people, who are perceived as having monotone voices, actually have a greater range of tone than most. However, because they use tone of voice atypically, people fail to notice that they are the opposite of monotone. The same may be true for their facial expressions.

When shown autistic and neurotypical people portraying basic emotions, neurotypical people understand neurotypical facial expressions better than autistic people’s facial expressions. So, autistic people show their emotions on their face differently than neurotypical people do. That leads to each misunderstanding how the other feels. [1]

[1: Footnote for those interested in the details of this research: The findings of this study are even more complex. Autistic people also had difficulty interpreting other autistic people’s emotions. That suggests there isn’t one consistent way that all autistic people express emotions, but multiple ways. So, an autistic person, another autistic person, and a neurotypical person may all express emotions differently, and will likely misunderstand each other’s expressions. Amazingly, that happens even with “basic emotions” that are supposed to be identical for all humans.]

Not Following the “Social Rules” of Expressing Emotions

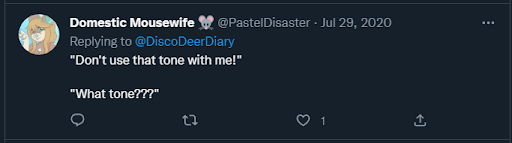

Cultures have different rules about who can express an emotion, how much, and in what situations. For example, when angry, children may not be allowed to speak as loudly or rudely to adults as an adult would (“don’t use that tone of voice with me, young man!”). We learn how to express and interpret our emotions from the people who raise us.

(It’s important to note that neurotypical people are the majority, so when we talk about the social norms of a culture, we are really talking about neurotypical social norms).

Neurodivergent people, especially autistic ones, do not absorb neurotypical social norms untaught. So why would we absorb the ones about how, when, and how intensely to express emotions?

For example, the intensity of anger a neurodivergent child expresses may match the intensity they feel, rather than the level that is considered socially appropriate. When others observe that child, they assume the child is following the norms and so their anger must be greater than they are expressing. When they “adjust upward,” they may conclude that the child feels a shockingly extreme amount of anger. The child may seem unreasonably angry. The adult may then become confused and judgmental towards the child.

So, there are reasons neurodivergent people might express emotions differently, but why aren’t they aware of it?

Here are some possible explanations.

Lack of Interoception

We often are disconnected from our bodies, unaware of the sensations coming from them. We lack “interoception,” the awareness of body sensations.

Neurodivergent people might have reduced interoception for several reasons.

While our attention is hyperfocused, we block out everything else, including internal sensations. As a child, I would focus so hard on writing that I wouldn’t notice I needed to use the bathroom. These days, I’m likely to come out of a three or four hour bout of hyperfocus hungry, having skipped my normal meal time. Learning to notice our body signals earlier and break out of hyperfocus sooner is a long process. I am still on this journey.

Some neurodivergent people endure training to ignore our sensory discomfort because our complaints are inconvenient to others. We then form a habit of blocking out feelings from our bodies.

Finally, some neurodivergent people might just be “wired” that way.

Alexithymia

Some neurodivergent people experience “alexithymia,” which means lack of awareness of our own emotions. That means others can observe signs of emotions the alexithymic person doesn’t know they feel.

Alexithymia is related to lack of interoception, probably because people often use interoceptive cues, like increased heart rate or a heaviness in the chest, to identify our emotions.

Imagine a neurodivergent person, April, has been asked to perform a task she doesn’t believe she can do, and feels anxious about it. Her heartbeat and body tension shoot up, and her tone of voice sounds angry. She knows she feels anxious, but she is unaware of the rest. Her neurotypical partner, Dave, hears her tone of voice and thinks she’s angry.

Like most people, April feels more than one emotion at the same time. She is also angry at having to do something impossible for her, and frustrated with herself about her own limitations. These feelings bleed into her body language and tone of voice. Because of her alexithymia, April is unaware of her frustration and anger, only her dominant feeling of anxiety.

In this case, April’s tone expresses anger and frustration she really feels. In a sense, Dave is right.

However, these are not the dominant or most important emotions she feels. Most of all, these are not the emotions she needs Dave to respond to. Dave, in seeing only April’s anger, misses the full picture. Misunderstandings still occur when one person is alexithymic.

Be careful not to assure a neurodivergent person you know is alexithymic. Only a minority of us are. Assuming we have secret hidden feelings we don’t know about – but you do – leads to assuming you know our feelings better than we do. That assumption is hurtful, and usually inaccurate.

In short…

Neurodivergent people do not necessarily feel the emotions our bodies seem to signal. We’re often unaware of this mismatch. We have to learn it exists by making sense of the reactions of other people, which can take years. Neurodivergent people are often misunderstood for this reason, as well as the reasons listed in my previous post.

Neurodivergent people come to expect our feelings and motivations to be misinterpreted, or even disbelieved. The next post in this series will describe how we respond to this constant threat hanging over all our interactions.

For More Information

We Don’t Know What Our Faces Are Doing by Jaime A. Heidel

Autistic People Often Can’t Detect Our Own Tone of Voice by Jaime A. Heidel

Autistic Body Language by Emma

Autistic Women and Facial Expressions by Sarah Reade

Research on Facial Expressions Changes the Way we Think About Autism by Connor Tom Keating and Jennifer Cook

Interoception – How do I Feel? by Cynthia Kim

Neurotypicals: Listen to Our Words, Not Our Tone by Ira Kraemer

Emily Morson

About the Author

Emily M. is a writer fascinated by the infinite variety of human minds. She grew up inexplicably different and was diagnosed as an adult with several forms of neurodivergence, including ADHD and an auditory discrimination disability. Feeling as if she were living life without a user's manual, she set out to create her own. In the process, she met other neurodivergent people on similar quests. She began working with them, advocating for inclusion, accessibility, and autism acceptance. Seeking to understand how neurodiverse minds work, she became a cognitive neuroscience researcher.

Her favorite research topic: what do children learn from their intense, passionate interests? Wanting to help neurodivergent people more directly, she trained as a speech/language therapist. Ultimately, she turned to writing, combining research with personal experience to explain autism and ADHD and champion acceptance – because everyone is happier when they are seen and accepted for who they are. She envisions a world where neurodiverse people have equal opportunities for education, loving relationships, and meaningful work.

She also blogs about autism and ADHD research at Mosaic of Minds. You can chat with her on Twitter: @mosaicofminds