Neurodiverse Communities Might Support Autistic People’s Health by Helping Them Cope With Minority Stress

Neurodiverse Communities Might Support Autistic People's Health by Helping Them Cope With Minority Stress

I recently saw a presentation by Dr. Monique Botha, research fellow at University of Stirling, organized and funded by the Autism Intervention Research Network on Physical Health (AIR-P). The talk focused on why autistic people have greater risk of physical and mental illness and what we can do about it. If you’d like to learn more about her research, look her up and ask her questions (Moniquebotha.com; Twitter: @drmbotha). The research discussed was financially supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. My post explains the key points of her talk. All images shown here come from her presentation (slides were sent to attendees after the talk).

Being part of a minority group that is seen negatively can harm people’s physical and mental health. The unpleasant experiences that people in these minority groups face increases their physiological stress, which in turn, puts them at risk of diseases. This process is called “minority stress.”

However, people in minority groups are not helpless in the face of minority stress. When they accept each other, identify with each other, and work together, that can reduce the effects of minority stress and benefit their health.

Autistic people are a minority of the population. They are viewed negatively (as less intelligent, capable, and likable than others). That means they are subject to minority stress.

However, research is only starting to take this possibility into account. Monique Botha is one of the researchers examining how minority stress affects autistic people’s health. She is also investigating whether they can help each other in the same ways members of other minority groups can.

Taking a minority stress perspective on autism is important for two reasons.

First, it gives us a useful explanation for why autistic people have higher rates of physical and mental illnesses. It lets us see – and change – how society and institutions affect autistic people’s health.

The minority stress perspective also shows how autistic people can support each other to improve their health – and why others should encourage them to do so.

Let’s delve more deeply into what we know so far about minority stress.

What minority stress do autistic people face? What are the consequences?

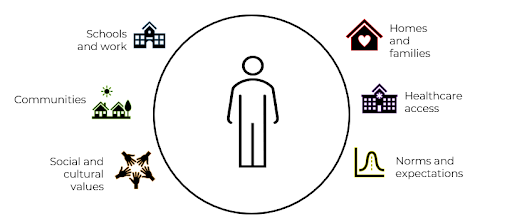

Like all humans, autistic people belong to:

- groups (like their families and neighborhoods),

- institutions (like school, work, church), and

- communities (like their hometown).

They seek help from another institution, the health care system, when they are sick.

Autistic people are taught the social norms and expectations of all these groups and judged by whether they succeed or fail to meet them. They are judged by how well their behavior fits the social and cultural values of their families, institutions, and broader communities. In other words, they are compared with the “good” child, student, friend, coworker, church member, patient, and so on. If they do not meet these expectations, the consequences can be severe.

Unfortunately, that is bound to happen, whether or not a person is diagnosed, because autism is defined by behavior that differs from social expectations.

And that’s before considering negative stereotypes about autism that all these people and institutions may have.

Above: A silhouette of a person stands in a circle. Around the circle, clockwise, are words with accompanying symbols. These represent the context that surrounds the person: “Homes and families” (represented by a house with a heart in it), “Health care access” (represented by a hospital building), “Norms and expectations” (represented by a bell curve graph), “Social and cultural values” (represented by a circle of hands), “Communities” (represented by two houses next to each other), and “Schools and work” (represented by a building).

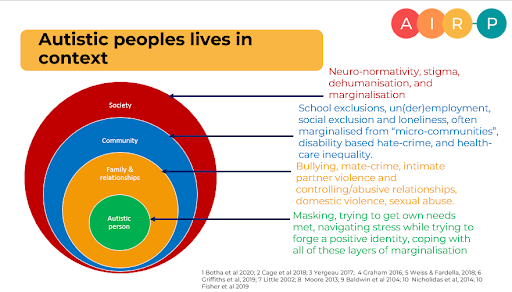

At the society and community level, autistic people are exposed to dehumanization and stigma. They are excluded from school, employment, medical practices, and more. On the level of personal relationships, they more often experience abuse of all kinds.

Above: Image shows a set of nested circles, each with an arrow to text of the same color as the circle that lists negative experiences that affect autistic people. The external red circle, labeled “Society,” → “Neuro-normativity, stigma, dehumanization, and marginalization.” The blue circle, Community, → “School exclusions, un(der)employment, social exclusion and loneliness, often marginalized from ‘micro-communities,’ disability-based hate crime, and health care inequality.” The yellow circle, “Family and Relationships,” → “Bullying, mate crime, intimate partner violence and controlling/abusive relationships, domestic violence, sexual abuse.” The innermost green circle, labeled “Autistic person,” → “Masking, trying to get own needs met, navigating stress while trying to forge a positive identity, coping with all these layers of marginalization.” Below, a set of references to research papers supporting and explaining these claims.

The central circle, “Autistic person,” highlights that part of the stress of living with these negative messages and experiences is trying to see oneself in a positive light, as a worthwhile human being.

We can easily see how facing these ordeals causes stress.

We know that autistic people:

- Die younger (at an average age of 53-58 compared to 70).

- Die more often of suicide, endocrine disorders, circulatory disease, nervous system disorders, and digestive disorders.

- Are more likely to have cardiovascular disease, type-II diabetes, and arrhythmia.

- Often experience depression, clinical anxiety, bipolar, and sleep-wake disorders.

In one study, two thirds of autistic people have thought of suicide, and one third have a history of suicide attempts.

How Minority Stress Harms People’s Health

Research on gender and sexual minority populations find that minority stress affects people’s health in three different ways:

- Direct Impact: Minority stress, like other forms of stress, directly changes how people’s bodies function. It can affect blood pressure, coronary disease, immune functioning, inflammation, and more.

- Indirect Impact: Some ways that people choose to cope with the negative emotions caused by minority stress harm their health further, such as alcohol and substance use.

- Even More Indirect Impact: When people experience minority stress in the health care system, they may be less likely to seek out health care when they need it. That avoidance results in worse health.

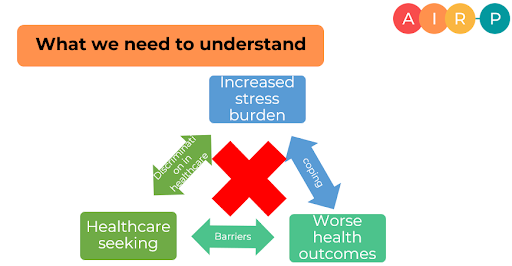

Here is another way to look at the problem of minority stress, which suggests ways to solve it. In diagrams like this, arrows are processes. Focus on the arrows, because they show where we can change things

Above: A triangle of boxes is shown: the top blue one says “Increased stress burden,” the left olive one says “Health care seeking,” and the right mint one says “Worse health outcomes.” An arrow labeld “discrimination in health care” links “health care seeking” with “increased stress burden.” An arrow labeled “barriers” connects “health care seeking” with “worse health outcomes.” Finally, an arrow labeled “coping” connects “increased stress burden” with “worse health outcomes.” In the middle, a red X symbolizes the need to disrupt these processes.

Research on gender and sexual minority populations find that minority stress affects people’s health in three different ways:

- Direct Impact: Minority stress, like other forms of stress, directly changes how people’s bodies function. It can affect blood pressure, coronary disease, immune functioning, inflammation, and more.

- Indirect Impact: Some ways that people choose to cope with the negative emotions caused by minority stress harm their health further, such as alcohol and substance use.

- Even More Indirect Impact: When people experience minority stress in the health care system, they may be less likely to seek out health care when they need it. That avoidance results in worse health.

Here is another way to look at the problem of minority stress, which suggests ways to solve it. In diagrams like this, arrows are processes. Focus on the arrows, because they show where we can change things

Helpful Ways People Cope With Minority Stress

People under minority stress often come together to create their own communities of support. For example, we often see people forming gender/sexual, racial, and ethnic minority communities.

These groups help people in a number of ways.

Belonging: First, these communities offer opportunities for connection with similar others. One element of this is a sense of belonging: not feeling fundamentally different and alone is incredibly powerful. Within autism communities, another important element is the opportunity to make friends with other autistic people, with whom they often felt an instant connection.

Self Image: These minority communities offer alternative, more positive ways to view oneself, which is good for mental health. At the very least, they support owning and taking pride in differences rather than hiding and feeling ashamed of them.

Sharing Resources: Members of minority communities often share resources. That can be especially important for autistic people, who are often unemployed.

Advocacy: Finally, minority communities often work together to create social change, from pushing back against stigmatizing stereotypes to campaigning for more legal rights.

Monique Botha and colleagues Bridget Dibb and David M. Frost (2022) asked 20 autistic adults around the world what they get from being part of autism communities. Participants said being connected to autistic communities led to “increased self-esteem, a sense of direction and a sense of community not experienced elsewhere.”

We are just starting to understand how benefits like these might help autistic people deal with minority stress and affect their health.

Monique Botha found that while autistic people with higher minority stress had worse mental health and well being, the degree to which they were connected with autistic communities moderated that. People who were more connected to autistic communities had better mental health and well being than people who were less connected.

However, one small study is not enough to understand the processes at work. Monique Botha wants researchers to work with autistic communities to understand how these communities can support autistic people’s health.

TL;DR

- Autistic people are a negatively viewed minority of the population. As such, they probably experience minority stress.

- Research (mostly from other minority groups) indicates that minority stress occurs in many contexts, including families, neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, churches, and more.

- Minority stress harms people’s physical and mental health in several ways, both directly and indirectly.

- The ways people respond to minority stress can reduce or increase its harmful effects.

- People dealing with minority stress can protect their health to some degree by participating in minority communities.

- We need to better understand how minority stress affects autistic people and how neurodiverse communities can help them protect their health.

Ways We Can help

Minority stress affects people from the broadest level of society as a whole, down to our individual relationships with friends and family. That means there are many ways we can reduce the stress on the autistic people in our lives.

As a society, we can…

- Reduce stigma: Let go of negative stereotypes about autism and autistic behavior, such as hand flapping or talking about intense interests. Replace these stereotypes with neutral and positive images that reflect autistic people’s variety and humanity.

- Improve health care access: Make sure health care professionals are trained to serve autistic people, and do not send them away.

- Combat bullying when it occurs: discourage it by providing negative feedback rather than ignoring it or treating it as socially acceptable.

- Judge School Performance and Employability Fairly: Judge performance at school, in job interviews, and at work by the ability to perform one’s duties, not by the ability to “talk oneself up” and “look good” doing it.

Above Image: Two silhouettes of hands reach out to each other. Each contains words in blue and red such as “us,” “respect,” “serve,” “help out,” “understand,” “thank,” “welcome,” “cooperate,” “interrelate,” and “unite.” Image from Max Pixel.

As individuals, we can…

- Reach out to autistic people – in our local community and beyond.

- Explore and share positive images of autism in conversation with others (“actually, Aunt Marge…”). Kind Theory can help with this.

- Help autistic people access accurate health information and medical care. Help them navigate through the system and get past barriers. Some autistic people bring trusted family and friends to act as a “translator” between them and their health care providers.

Stay tuned

Dr. Botha’s presentation also explored how autistic people’s ways of coping with minority stress affect their health. Specifically, autistic people decide how much to hide their autism and pretend to be neurotypical – and that choice has consequences for their mental health. These insights will be discussed in my next post. Please stay tuned.

Further Reading

Links in the titles go to free, open-access papers. The DOI links go to the versions on the publisher’s website, which may or may not be available for free.

***Botha, M., and Frost, D. M. (2020). Extending the Minority Stress Model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Society and Mental Health, 10(1), 20-34. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869318804297.

Botha, M., Dibb, B., & Frost, D. M. (2022). “It’s being a part of a grand tradition, a grand counter-culture which involves communities”: A qualitative investigation of autistic community connectedness. Autism, 26(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221080248

Presentation: Botha, M., Dibb, B., Rusconi, P., & Frost, D. M. (2021, May). Autistic community connectedness as a moderator of the effect of minority stress on mental health in the autistic population [Conference presentation]. International Society for Autism Research 2021 Virtual Annual Meeting.

This paper lays out the minority stress model in the context of LGBT+ health: Meyer, Ilan H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674-97.

References

Note: Links in the title of the papers go to open access pdf’s. The DOI’s link to the publisher’s website, which may or may not make them available for free.

Over two-thirds of autistic people have thought of suicide, while one-third have a history of attempts: Cassidy, S., Bradley, L., Shaw, R., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 9(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-018-0226-4

Direct impact of minority stress on biological functions: Flentje, Annesa, Heck, Nicholas C., Brennan, James Michael, Meyer, Ilan H. (2020). The relationship between minority stress and biological outcomes: A systematic review. J. Behavioral Medicine 43:673–694 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00120-6

Minorities may experience minority stress in healthcare settings, which in turn may lead to avoiding such settings: Glick, J. L., Andrinopoulos, K. M., Theall, K. P., & Kendall, C. (2018). “Tiptoeing around the system”: alternative healthcare navigation among gender minorities in New Orleans. Transgender Health, 3(1), 118-126. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2018.0015

Autistic people in a population-based cohort study died younger, at mean age 53-58 vs. a mean age of 70: Hirvikoski, Tatja, Mittendorfer-Rutz, E., Boman, M., Larsson, H., Lichtenstein, P., Bolte, S. (2016). Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry 208 (3), 232-38. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160192

Smoking and substance use as ways of coping with minority stress: Livingston, N. A. (2017). Avenues for future minority stress and substance use research among sexual and gender minority populations. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(1), 52-62. 2, https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2017.1273164

Minority stress offers the potential for community interconnectedness and support: Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

Health care access is limited, and autistic people report barriers such as hostility from staff: Nicolaidis, C., Raymaker, D. M., Ashkenazy, E., McDonald, K. E., Dern, S., Baggs, A. E.V., Kapp, S., Weiner, M., & Boisclair, W. C. (2015). “Respect the way I need to communicate with you”: Healthcare experiences of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism, 19(7), 824-831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315576221

Autistic people are more likely to have non-communicable diseases: Weir, E., Allison, C., Warrier, V., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2021). Increased prevalence of non-communicable physical health conditions among autistic adults. Autism, 25(3), 681-694. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320953652

Emily Morson

About the Author

Emily M. is a writer fascinated by the infinite variety of human minds. She grew up inexplicably different and was diagnosed as an adult with several forms of neurodivergence, including ADHD and an auditory discrimination disability. Feeling as if she were living life without a user's manual, she set out to create her own. In the process, she met other neurodivergent people on similar quests. She began working with them, advocating for inclusion, accessibility, and autism acceptance. Seeking to understand how neurodiverse minds work, she became a cognitive neuroscience researcher.

Her favorite research topic: what do children learn from their intense, passionate interests? Wanting to help neurodivergent people more directly, she trained as a speech/language therapist. Ultimately, she turned to writing, combining research with personal experience to explain autism and ADHD and champion acceptance – because everyone is happier when they are seen and accepted for who they are. She envisions a world where neurodiverse people have equal opportunities for education, loving relationships, and meaningful work.She also blogs about autism and ADHD research at Mosaic of Minds. You can chat with her on Twitter: @mosaicofminds

Recent Edits (2 January, 2023):

- Changed font size of the introductory paragraph

- Added ALT Text for images

- Added Kind Theory link to “As Individuals, we can…”