To Stay Healthy, Should You Show You’re Autistic Or Not? Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

To Stay Healthy, Should You Show You’re Autistic Or Not? Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

This post is part 2 of a series inspired by Monique Botha’s presentation about how minority stress harms autistic people’s physical and mental health. The first post explained that autistic people are a minority of the population that is viewed negatively. Therefore, they experience additional “minority stress,” which reduces their health. Today’s post focuses on the pros and cons of a common way autistic people choose to cope with minority stress: masking (hiding that they are autistic).

People who belong to minority groups that are viewed negatively cope with that in different ways. Some of these are positive, such as finding communities of similar people. Others, such as alcohol and substance abuse, are negative.

The biggest choice is whether to show or hide that they are a member of that minority group.

When it is possible, people often choose to hide. For example, someone may choose to wear an in-ear hearing aid that is invisible to others. A person with low vision may choose not to use a cane in familiar places where they can navigate unaided.

When it comes to autism, visibility is complicated.

Autism is an “invisible disability” in the sense that there are no physical features that signal autism, as there are for Down syndrome. [1] Autism is “invisible” in another way: behavior that is natural to an autistic person is rarely seen as “autistic” unless people know about the diagnosis. Instead, it is perceived as “weird,” “stupid,” “annoying,” or “cringy.”

Yet, autism can lead people to behave visibly differently. They may flap their hands or walk on tiptoes. They may appear expressionless even when happy. They may talk at great length about their passionate interests, even after their listener has lost interest. In this sense, autism is highly visible.

Autistic people are trained from an early age by parents, teachers, and therapists to hide such behavior and act like neurotypical people. Hiding natural behavior to act “normal” is called “masking.” Some people become so good at masking that even psychologists doubt whether they are really autistic.

So, when people choose how visibly autistic they want to be, they are choosing how much to mask.

[1] People have proposed certain physical features are characteristic of autism. Some, such as looking younger than one’s age, are anecdotal. Others, such as having an unusually large head as a baby, are based on research evidence. These might be more common among autistic people than others, but every autistic person doesn’t have them.

What Happens When You Make Your Autism Visible?

Above image, originally from Room to Thrive, shows a row of apples, three green and one red, with a quote from Brene Brown: “If I get to be me, I belong. If I have to be like you, I fit in.”

Being visibly autistic makes people a target of outside hostility, prejudice, and active discrimination.

It starts early in life, with higher rates of abuse and neglect from parents and bullying by peers. Elsewhere, I’ve written about what it’s like growing up constantly being told what you’re doing is wrong. Bullying continues throughout life, in the workplace and in interpersonal relationships.

So one might think, why would an autistic person choose to make themselves visible?

First, people do it for altruistic reasons. They want to show that autistic people are people, just like everyone else, and deserve to be treated as such.

Second, we know from other minority groups that showing that you’re not intimidated by bullying and negative stereotypes takes away some of their power. Showing others that it’s possible to survive the consequences of being visible can inspire others to take the same risk. Once enough people make the choice to become visibly autistic, it becomes more familiar and less scary to neurotypical people, and they become less hostile. This is the logic behind “out and proud” and reclaiming words that have been used as slurs.

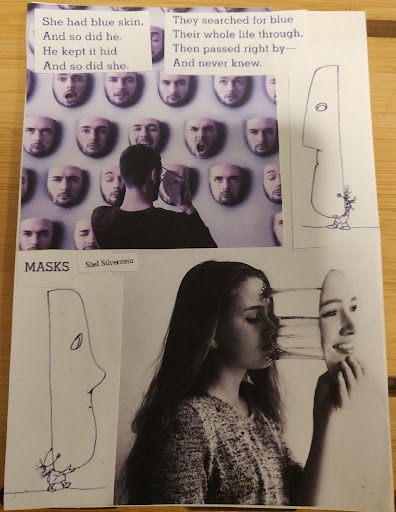

Above: Collage by me, “Masks.” It features the poem Masks by Shel Silverstein and associated art; a painting of a man examining masks showing different facial expressions; and a painting of a woman attempting to pull off a mask that is stuck to her skin.

Let’s start with the obvious. When you mask, you face less external harm. However, there are considerable internal costs.

First, the less you act like yourself, the easier it is to lose touch with who you are. When this process begins young – as it does for many autistic people – it can be hard to develop a secure sense of self.

Second, as Monique Botha notes, when you spend your life measuring yourself against stereotypes about people like yourself, it’s easy to internalize them.

The most stressful part of hiding is the experience of being “in the closet.” When an autistic person fears that “if people knew what I am really like, they would reject me,” it is not imposter syndrome; it is simple fact. And it weighs on you.

Even when people in hiding are accepted, they can’t get the full emotional benefit, because the connection isn’t real. They know, “it’s not really me that they love.”

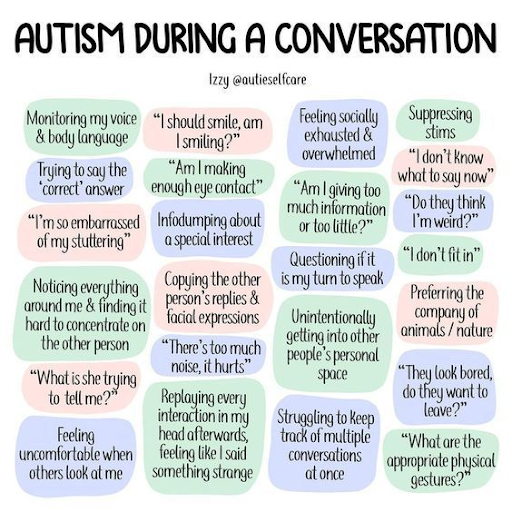

As Jillian Enright puts it, “our brains are still different beneath our masks.”Finally, masking requires continual self monitoring to make sure one’s behavior is acceptable. An everyday conversation can be exhausting, as one asks oneself, “Am I making the right amount of eye contact?”, “am I giving too much information or too little?”, “what facial expression and gestures should I be making right now?”, “am I successfully avoiding stimming?” and so on. [2]

Above image, by Izzy (@autieselfcare), is titled, “Autism During Conversation.” It consists of blue, green, and pink blobs, each containing a thought. In addition to the examples mentioned above, these thoughts include: “Monitoring my voice and body language,” “I should smile, am I smiling?”, “copying the other person’s replies and facial expressions,” “what are the appropriate physical gestures?”, “they look bored, do they want to leave?”, “Do they think I’m weird?”, and more.

This constant vigilance is physically and mentally exhausting, and autistic people report that it can lead to burnout.

All this emotional stress weighs on both mind and body, leading to more mental and physical health problems.

Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t

Monique Botha sums autistic people’s dilemma up as follows: whether you choose to mask or not, minority stress harms your health. “Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

Botha’s research delves further into the tradeoffs autistic people make when they make this choice.

Botha surveyed 111 autistic people worldwide, who were 36 years old on average. As she acknowledges, this was not a representative sample. In this group, as many as 72% were female, while only 70% were officially diagnosed. As is unfortunately common in research, 85% were white.

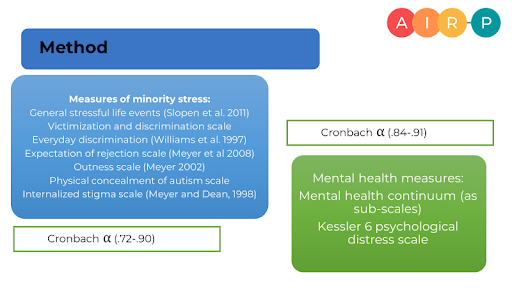

Participants were given seven different questionnaires measuring the general and minority stress they experienced, how “out” they were, and how much they experienced and expected to experience stigma and discrimination. “Outness” means disclosure to friends, family, peers, and work colleagues. They were also given questionnaires measuring their mental health. The image below lists the measures used.

Above: Measures of minority stress included: General stressful life events (from Slopen et al., 2011), Victimization and discrimination scale, everyday discrimination (Williams et al., 1997), expectation of rejection scale (Meyer et al., 2008), outness scale (Meyer, 2002), physical concealment of autism scale, and internalized stigma scale (Meyer and Dean, 1998). These have a Chronbach’s alpha of .72-.90. Measures of mental health included a mental health continuum (as subscales), and the Kessler 6 psychological distress scale. These have a Cronbach’s alpha of .84-.91. Chronbach’s alpha is a measure of reliability, and .70 or higher is considered acceptable in social science research.

Botha found that:

- Experiencing discrimination hurts: The more people experienced victimization and everyday discrimination, the lower their emotional and psychological well-being. The more everyday discrimination people faced, the greater their psychological distress.

- Greater outness predicted worse psychological well-being and psychological distress.

However, concealment also hurts:

- The more people expected to be rejected and concealed their autism, the worse their social well-being.

- Internalized stigma predicted worse emotional well-being and greater psychological distress.

In other words: both disclosing and concealing autism are related to poor mental health outcomes. Monique Botha’s participants were “damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

(Botha mentions that research shows a similar double bind for LGBT people).

What Can We Do?

I am not going to tell autistic readers to what extent they should mask. Deciding how visible to make themselves is a personal choice that quite literally affects their safety.

Instead, I will address myself to readers in general about how to help other autistic people in their lives. You might be family, friends, teachers, doctors, therapists, or community members. You may be non-autistic or autistic.

We can make it safer for autistic people to be visible by standing with them, literally and figuratively. Give your loved ones safety in numbers.

- Make it acceptable to be autistic in public: Be friendly in public with them while they avert their gaze, or flap their hands, or otherwise behave in ways that are atypical but natural to them.

- Show that bullying is socially unacceptable: Interrupt any bullying you witness.

- Change the stereotypes and support your loved ones: Provide positive countermessages about the autistic people in your life. Kind Theory can help.

- Don’t tell autistic people, “just be yourself.” Pete Wharmby explains: It might be safe to unmask with you, but autistic people have good reasons to fear doing so with others. You may be underestimating how much stress the autistic person may express when they drop the mask, and how negatively others may react.

- Let the autistic people in your life unmask in private. This may be an adjustment for both of you, as they may act quite differently. Ask questions and listen to the answers – this can show them you care and spark connection. It can also help you understand what they’re experiencing and how to help.

To be healthy and happy, we all need people with whom we can take off the mask and be ourselves. I invite you to be that person.

[2] We know the most about masking when it comes to autism, but people with ADHD often mask, too – including me. ADHD Alien has a great comic about it.

Further Reading

Thanks to autistic researchers, there is a growing area of research focused on masking. This is a topic that deserves its own post (or many). Below are some resources on what masking is like and how it affects people.

Personal Accounts

What Happens When You Don't Mask

Speech (without a title) by Julia Bascom (Content Warning for graphic discussion of bullying and self-harm)

What If? by Ischemgeek

Growing Up Wrong by Emily M.

Masking

- What is Autism Masking by Jill Feder: An exhaustive explanation of the many negative consequences of masking, including several not discussed here.

- I Was Masking So Long, I Lost Myself – Jillian Enright

- The Price of Autistic Invisibility by Jae L.

- Indistinguishable from peers: An introduction by Kassiane A.

- Indistinguishable from peers means: You don’t have autism related problems by Kassiane A.

- Autistic Burnout, Explained by Sarah DeWeerdt in Spectrum News

References

- Botha, M., Dibb, B., & Frost, D. M. (2022). “Autism is me”: an investigation of how autistic individuals make sense of autism and stigma. Disability & Society, 37(3), 427-453.

- Botha, M., & Frost, D. M. (2020). Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Society and mental health, 10(1), 20-34.

- Cage, E., Cranney, R., & Botha, M. (2022). Brief report: Does autistic community connectedness moderate the relationship between masking and wellbeing?. Autism in Adulthood, 4(3), 247-253.

- How people mask: Cook, J., Crane, L., Hull, L., Bourne, L., & Mandy, W. (2022). Self-reported camouflaging behaviours used by autistic adults during everyday social interactions. Autism, 26(2), 406-421.

- Cook, J., Hull, L., Crane, L., & Mandy, W. (2021). Camouflaging in autism: A systematic review. Clinical psychology review, 89, 102080.

- Libsack, E. J., Keenan, E. G., Freden, C. E., Mirmina, J., Iskhakov, N., Krishnathasan, D., & Lerner, M. D. (2021). A systematic review of passing as non-autistic in autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(4), 783-812.

- Miller, D., Rees, J., & Pearson, A. (2021). “Masking is life”: Experiences of masking in autistic and nonautistic adults. Autism in Adulthood, 3(4), 330-338.

Emily Morson

About the Author

Emily M. is a writer fascinated by the infinite variety of human minds. She grew up inexplicably different and was diagnosed as an adult with several forms of neurodivergence, including ADHD and an auditory discrimination disability. Feeling as if she were living life without a user's manual, she set out to create her own. In the process, she met other neurodivergent people on similar quests. She began working with them, advocating for inclusion, accessibility, and autism acceptance. Seeking to understand how neurodiverse minds work, she became a cognitive neuroscience researcher.

Her favorite research topic: what do children learn from their intense, passionate interests? Wanting to help neurodivergent people more directly, she trained as a speech/language therapist. Ultimately, she turned to writing, combining research with personal experience to explain autism and ADHD and champion acceptance – because everyone is happier when they are seen and accepted for who they are. She envisions a world where neurodiverse people have equal opportunities for education, loving relationships, and meaningful work.She also blogs about autism and ADHD research at Mosaic of Minds. You can chat with her on Twitter: @mosaicofminds