Organizing Doesn’t Have to be an Ordeal

Organizing Doesn't Have to be an Ordeal

How I’m transforming routines and planning devices from shame trigger to support

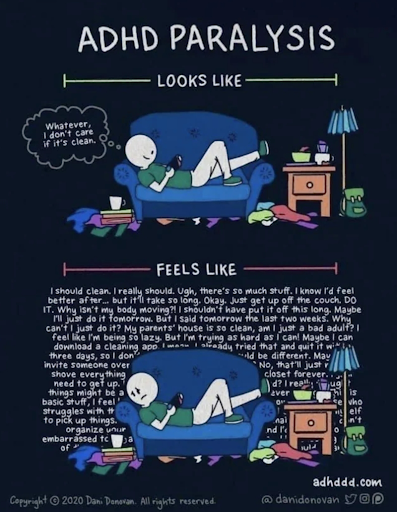

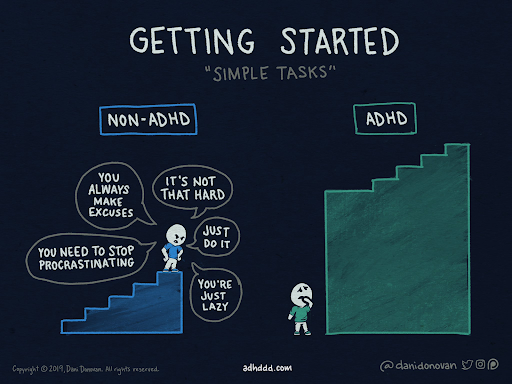

People with ADHD and other kinds of executive dysfunction struggle to manage our time, space, and tasks. To accomplish what our brains can’t do naturally, we turn to external structure. We try planning devices (like calendars and planners), routines, and technology (alarms).

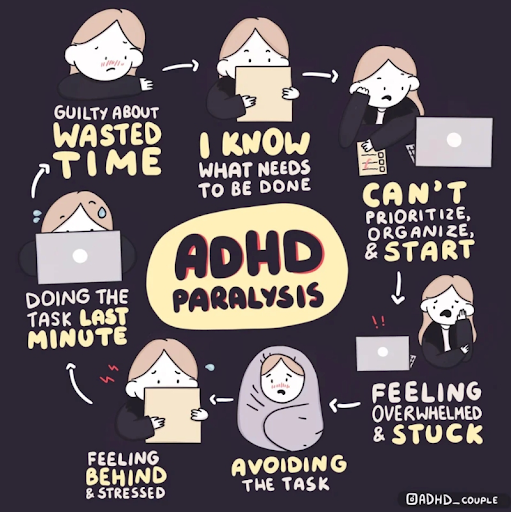

Ironically, ADHD interferes with attempts to remediate or work around it.

Too often, we try systems and abandon them too soon, because even while using them, we don’t accomplish everything on our to-do list. For example, I have boxes of old planners accumulated while developing methods for using them effectively. My phone has a few apps I actually use, and dozens that I’ve tried and abandoned.

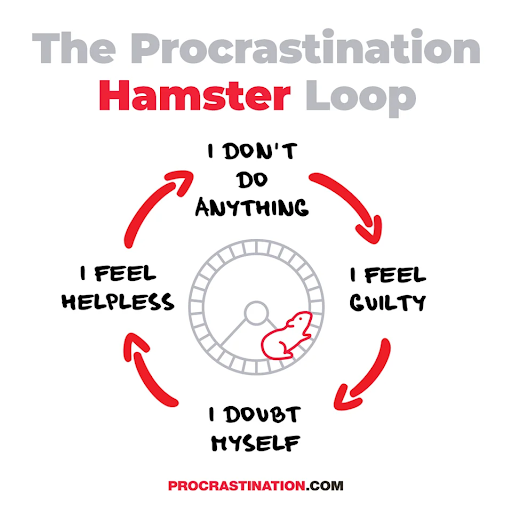

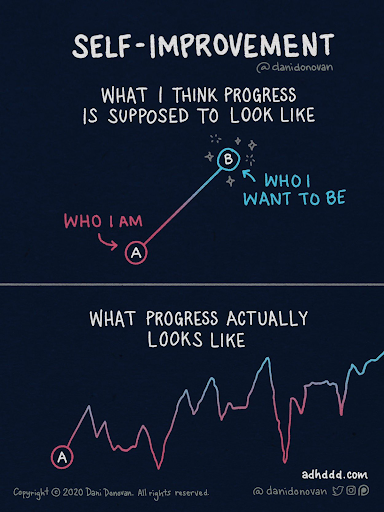

People with ADHD often interpret these disappointing self-improvement efforts as “failure.” We feel ashamed, and ever more discouraged. The next time, it’s harder to get started and we abandon our system even sooner.

This is a vicious cycle that repeats daily for a lifetime. It saps our strength and even drives us into depression.

What if this vicious cycle doesn’t have to happen?

We can influence part of this ADHD Cycle of Pain and Paralysis: our thoughts, feelings, and reactions. When we have difficulty using structure, how do we interpret it? What do we learn? Do we believe the voice telling us we’re helpless and give up? Or, do we adjust our plans and try again?

To interrupt the Cycle of Pain and Paralysis, I’m trying different mindsets.

I realize I’ve learned to see structure as a set of onerous demands imposed on me by other people’s expectations. For example, instead of anticipating guests with joy, I may dread their judgment of my messy home. I’m not the only one. Who hasn’t shoved a pile of laundry or miscellaneous objects into the closet before guests arrive?

I don’t want to live that way any more. Relying on fear and shame to be productive hurts, and long-term, it doesn’t even work.

So, I’m experimenting with new ways of looking at organizing my time and space. I’m adopting three mindsets: taking on the personas of a Maker of Beauty, a Scientist, and a Creator. From these perspectives, organizing helps me take care of myself, please my senses, and set myself up for creativity.

Here’s how these 3 mindsets work – and how they’re improving my mental health.

What this is Not

Some people might bristle at the word “mindset,” which has been abused by people trying to sell quick fixes or deny that disability is real. That’s not what I mean.

I’m not trying to “fix” myself with a productivity “hack.” I still have ADHD, a disability of executive function, no matter how I choose to view it. More importantly, I’m not something to be “fixed” in the first place.

Instead, I’m changing my relationship to cleaning and organizing.

Many people with ADHD have learned damaging, shame-based ways to approach organizing. We may absorb these attitudes from our families, communities, or the media. To unlearn this baggage, we need to replace it with something better.

That’s where the Maker of Beauty, the Scientist, and the Creator come in. These ways of being are easy to understand, easy to visualize, and encouraging.

Mindset 1: Be a Maker of Beauty, Joy, and Safety

The Challenge: Mess

Like many people with ADHD, I have a messy home. I also rarely cook. These facts are related. (Cooking dinner seems more onerous when you have to scrub pots and pans first).

Mess accumulates in my home for several reasons.

First, when I am interrupted midway through a task, I forget to finish and clean up. For example, when I’m interrupted while removing a dish from a kitchen cabinet, I leave the cabinet door open. Later, I walk into it, hitting my head on the corner. Ouch!

Second, I don’t notice all the small spills I make while cooking, especially those on the floor and under the cabinets. The stains build up until suddenly, the whole floor looks dirty.

Finally, I’m unsure when to do irregular, widely-spaced chores, such as scrubbing sinks, washing bedding and towels, or cleaning out the refrigerator. Thus, I tend to wait for visible, urgent signs that the time has come. If I’m running out of clean socks, it’s time to do laundry.

That urgency also motivates me. It’s the same principle that leads some students to start writing essays at the last minute.

The problem with cleaning when a mess has already built up is that messes tend to pile up suddenly, dramatically, at the most inconvenient times – usually, when a deadline looms and everything but working, eating, and sleeping goes by the wayside.

When I see accumulated mountains of mess, I dread cleaning them up – so I procrastinate.

Thus, maintaining my body and home can feel like a constant cycle of playing catch-up.

I rarely get to simply enjoy an empty sink or uncluttered desk.

I often forget that there even are rewards.

The Change: Creating a Home

I may not like the process of organizing my home and life, but I love the results.

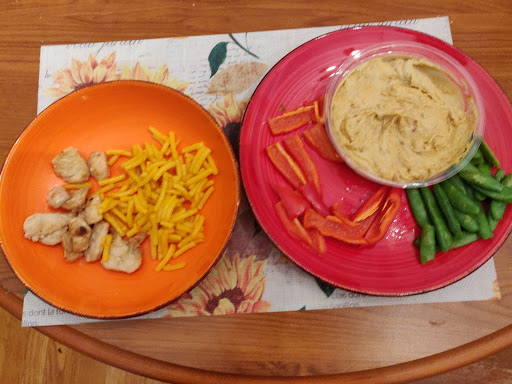

- I feel nourished and worthy when I sit at a clean dining table eating a warm, colorful home cooked meal, attending to the taste and texture instead of a device. For example, I savored this meal below:

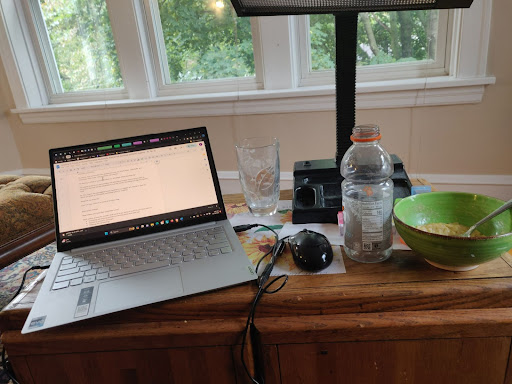

Who wouldn’t rather sit down in front of that than in front of the scene below?

That isn’t even a table. Empty bottles and glasses litter the cramped surface. A computer and light box crowd out the actual food. Not very inviting.

- I love leaving home without rushing, because I’ve prepared all the items I need and made my transportation plans the day before–allowing extra time.

- The only thing as inviting as a brand new blank notebook is an empty writing surface.

- I feel a sense of clarity and accomplishment when I finish cleaning something.

It’s hard to remember these simple joys. Yet, imagining these moments of calm and pleasure make the mountain of cleaning look more like a hill.

I have to continually remind myself that cleaning and decluttering is self care. And the times when I feel like doing it least are the moments when I need it most.

My mother’s home inspires me. Although cluttered, it feels warm, comfortable, and welcoming. When I visit, I feel nourished and cared for.

I want to create a home that makes me, and ideally others, feel comfortable and welcome.

I also want to create a place of refuge where I can recover from the overwhelming neurotypical world.

Such a home probably won’t look like the cover of Martha Stewart Living. It might even look cluttered or messy to some.

And really, that’s fine.

I’m teaching myself what I wish I’d learned as a child: to clean where I want, when I want, as much or as little as I want – for my own sake. I’m learning to make a home.

Mindset 2: Be a Scientist

The challenge: Inconsistency

My biggest difficulty managing my ADHD brain is that I stop using most organizational systems, at least temporarily, and then have difficulty re-starting or replacing them.

Sometimes, I forget to use these systems in the first place.

Sometimes, they don’t meet my needs and I stop using them.

Finally, sometimes they help me until an urgent deadline looms or a crisis strikes, requiring all my time and energy. Then, anything that takes too much time or effort to maintain, or isn’t physically present where I’m working, falls by the wayside.

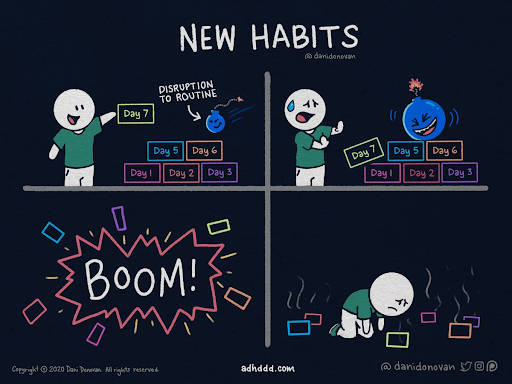

When I stop using a habit or tool, I feel as if I’ve failed. Yet another unused app on my phone or half-filled planner gathering dust. I lose momentum and struggle to restart.

I stopped using habit trackers and sticker charts because they only increased my shame. They also didn’t work. A skipped day here or there turned into giving up.

Some of the habits I’ve tried, which theoretically would help me, have never “taken.” I’ve yet to consistently meditate and look at my planner first thing each morning. I’ve never managed to consistently do a specific aerobic exercise at a specific time each day.

It took a while – and a lot of reading the Zen Habits blog – to understand what was happening.

With ADHD, building a lasting habit is not about continuing a habit once started. It’s about restarting.

You’ll inevitably fall off the wagon when life gets hard. Everyone does.

Re-starting a habit is hard. Even neurotypical people skip a day here or there, feel discouraged, and have difficulty starting over. That’s why so many people stop following their New Year’s resolutions, diets, and plans to go to the gym.

The Change: Treat Your Life as an Experiment

Thinking like a scientist draws on my natural curiosity and restores my hope and sense of control.

When I attempt to establish a habit or incorporate an organizational tool, it becomes an experiment. When I run into difficulty and skip a day, I observe the situation and make a hypothesis about what obstacle got in the way. Next, I come up with a potential solution, test it out, and observe the results.

From a scientist’s point of view, a missed day is not a failure, but an opportunity to learn. An inconsistency is just a data point.

With this data, I can discover what works for me longest. For example, I can compare how long I used the Clever Fox planner, the Passion Planner, and my own ever-improving bullet journaling system.

A Scientist doesn’t become discouraged when life changes (such as moving or changing jobs) force us to adjust our organizational systems. A Scientist expects frequent tinkering to be part of the great experiment of living.

As a Scientist, I assume that finding strategies that help me make the most of my brain will be an iterative, lifelong process.

Thinking like a Scientist motivates me to keep trying, track my progress, and celebrate small wins.

Mindset Three: Be a Creator

If you read books or blogs about how to write, you’ll find accounts of famous writers who insisted on writing in quirky places, at peculiar times, with unusual accessories.

Places:

- Maya Angelou wrote in a spartan hotel room.

- Gertrude Stein liked to write as a passenger in the car while her partner drove around town.

- Tolstoy and Mark Twain worked in a locked study, which no one was allowed to enter.

- Famous authors wrote standing, lying down, or taking a walk.

Times:

- Many famous writers wrote at the same time every day, until they reached a certain amount of time or word count. Trollope was famous for writing with his watch in front of him, aiming for 250 words every quarter hour.

Accoutrements:

- Schiller deliberately wrote with rotting apples in his desk drawer (which I don’t recommend).

- Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss, would try on one of his hundreds of hats when he needed inspiration.

- John Steinbeck kept exactly 2 dozen perfectly sharpened pencils of a specific brand on his desk.

These writers have good reason for insisting on an idiosyncratic routine: to create a container in space and time for their writing.

They’re setting the stage. Getting into the right mindset. Letting go of the concerns and emotions of the day so they can enter another world.

This is an immense mental transition. It requires abundant mental energy and intense focus to make words flow. Some people find it extremely difficult, and others can’t do it at all.

It’s no surprise that writers find ways to mark the transition between mental states.

Writers harness the brain’s gift for associative learning. When you consistently write in a specific place at a particular time, you start associating that place and time with writing. Ritual works in a similar way. For example, some religions signal the start of a ceremony by coming to a special place and lighting a candle.

As Steven King puts it,

The cumulative purpose of doing these things the same way every day seems to be a way of saying to the mind, you’re going to be dreaming soon.

I suspect writers are not the only people with creative rituals. Practitioners of other arts and crafts probably do, too. At the very least, they set aside dedicated space, however small.

For me, being in an empty space helps clear the stress from my mind and body, letting me focus on the words and images in my head. When I’m surrounded by visual clutter, I feel weighed down and overwhelmed. It’s as if my brain were a browser and each extra piece of paper, envelope, or coffee mug around me feels like a tab – demanding mental energy I need for writing.

Thus, cleaning and organizing become necessary for my creative practice. That changes the purpose of organizing from “what looks good” or “what will people think?” to “what will help me create?”

Even if the actions are similar, it feels completely different.

As a writer and occasional artist, I clean and organize to create a space that inspires and focuses me. I am also experimenting with creative rituals to find out how that space should look, sound, and feel.

My own favorite creative ritual involved jumping out of bed every morning to sit at my computer, drink coffee, and write the shortest possible microfiction in response to a daily prompt. Using a prompt narrowed down the infinite field of possible topics, making it easier to start. It was also interesting to see how differently each of us used the same prompt. My goal, to “get as close to 100 words as you can,” was challenging, yet flexible enough to achieve regularly. Best of all, I shared the ritual with friends. I knew they were probably writing at the same time. We’d read and comment on each other’s creations later that day. Having a guaranteed, appreciative audience was incredibly motivating.

I invite you to find a ritual that inspires you.

Everyone’s needs are different, so your ritual may look different than mine. When in Scientist mode, try different settings – light, time of day, background music, presence of other people, etc –to discover what makes creating easiest and most comfortable. Ask yourself, as Toni Morrison does:

What do I need in order to release my imagination?

Consider what time makes it easiest to create. Most famous writers seem to prefer morning and early afternoon, when fully alert. A few prefer writing at night and even while drunk. As much as you can, try to build your schedule around protecting your most productive hours.

Ironically, you’ll need to manage your time to give yourself the opportunity to enter creative flow, a state where time doesn’t exist.

Your ideal creative space might look messy to other people. Your ideal creative schedule might inconvenience some people.

It doesn’t matter. The scaffolding for your creative life only needs to make sense to you.

We often think of structure as the enemy of creativity. We may associate it with strict bosses; bureaucratic forms; and unimaginative teachers who only care about format and handwriting. However, when you choose the constraint based on your own needs, it creates a flower bed where your ideas can grow and flourish..

Your Own Mindset

Have you tried these, or other, mindset changes about structure? What changed for you?

Have you discovered any helpful mindsets not mentioned here?

Do you have a creative ritual? What does yours look like?

To share your own experiences, compare notes, or ask questions, comment here. You can also continue the conversation on Kind Theory’s Facebook and LinkedIn pages.

This post was brought to you by Dani Donovan and her relatable, insightful cartoons about ADHD.

Emily Morson

About the Author

Emily M. is a writer fascinated by the infinite variety of human minds. She grew up inexplicably different and was diagnosed as an adult with several forms of neurodivergence, including ADHD and an auditory discrimination disability. Feeling as if she were living life without a user's manual, she set out to create her own. In the process, she met other neurodivergent people on similar quests. She began working with them, advocating for inclusion, accessibility, and autism acceptance. Seeking to understand how neurodiverse minds work, she became a cognitive neuroscience researcher.

Her favorite research topic: what do children learn from their intense, passionate interests? Wanting to help neurodivergent people more directly, she trained as a speech/language therapist. Ultimately, she turned to writing, combining research with personal experience to explain autism and ADHD and champion acceptance – because everyone is happier when they are seen and accepted for who they are. She envisions a world where neurodiverse people have equal opportunities for education, loving relationships, and meaningful work.

She also blogs about autism and ADHD research at Mosaic of Minds. You can chat with her on Twitter: @mosaicofminds