How Neurodiverse Communities Changed My Life (And Might Improve Yours, Too!)

Above: Word cloud, entitled Neurodiverse Community, in the shape of two hands forming a heart in the space between their open palms. The title is in a dark reddish-pink while the other words are black against a white background. Words include the names of a variety of forms of neurodivergence, including autism spectrum, ADHD, dyslexia, discalculia, schizophrenia, Tourette syndrome, bipolarity, and more. Image from Shutterstock.

How Neurodiverse Communities Changed My Life (And Might Improve Yours, Too!)

I discovered neurodiverse communities by accident. It was 2008 and I was in college, desperately trying to understand why life seemed so much harder for me than for those around me.

At that point, I wasn’t diagnosed with anything. That wasn’t because I had developed typically. In the early 1990s, when people thought ADHD meant hyperactive and male, my preschool teachers suggested I, a not-particularly hyperactive girl, should be tested for ADHD. They didn’t know what to do with a child who couldn’t throw or catch or cut with scissors, who wandered out of line to dance, who “zoned out” and talked nonstop and cried in class. They worried about how I would “fit in” in kindergarten. However, my parents ignored their advice. They did not trust teachers who ignored my strengths. The teachers couldn’t explain how a diagnosis could benefit me or what services I needed.

So, I simply grew up knowing I was different. I talked, read, pretended, and felt more than other kids around me. I was the only child in the neighborhood who had allergies or meltdowns. That’s the thing about growing up undiagnosed: you’re still different, you just don’t know why. Neither does anyone else.

In college, I was perpetually tired and stressed. I couldn’t live up to the myth of the ideal college student, who does many things and does them all well. My classmates and dormmates generally did. They were juggling their classes, friendships, multiple activities, work, study, jobs, and campus events, running on only a few hours of sleep per night — and they seemed relatively content. I was overwhelmed just with turning in homework on time and spending unstructured time with friends. I had left the school orchestra and stopped attending plays and parties. Why did I seem so much more exhausted while doing so much less?

Because my younger sibling had been diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome when I was a teenager, I knew being neurodivergent [1] can make life harder. Some things most kids have to be taught, he learned effortlessly (he taught himself to read at age three). However, other things most kids are expected to pick up on their own, he needed people to explain (like social conventions). Similarly, I thought, my classmates, must have learned something I hadn’t. I just had to discover what it was.

In 2008, the term “neurodiversity” had yet to reach the media. Most information was written by researchers, teachers, and clinicians to help parents and teachers. It’s hard to recognize oneself in descriptions like these, even when the diagnosis fits. However, there were a few bloggers writing from the inside and posting on a few discussion forums, such as Wrong Planet. I read avidly, then began talking with the writers.

It led me to pursue an evaluation. It also changed my life. Here’s how.

I wasn't the only one

I adored Lynne Soraya’s blog on Psychology Today, Aspergers Diary. It made me feel less alone.

She was the first person I’d ever heard talk about sensory experiences.

Like me, she felt overwhelmed in crowded stores, wanted to flee, and felt tired afterward.

Like me, she found loud noises painful. For her, it was children talking in her childhood classroom. For me, it was off-key singing and the clang and scrape of metal (such as pots and pans).

When you’re the only person who experiences something, you start to wonder if it’s real. Especially if people tell you things like, “it’s not that loud.”

Her stories taught me two vital things.

My experiences were real.

And I wasn’t the only one who felt this way.

I learned about myself

I have extremely uneven skills. Being neurodivergent and diagnosed late, I’ve spent most of my life trying to understand why some things are so hard, especially when similar ones are easy.

- How is my hearing so sensitive that loud noises hurt and sudden ones startle me, yet so muddled that I can’t understand what people are saying with music or running water in the background?

(The culprit: difficulty with auditory discrimination. That means, with the normal amount and quality of the sound signal, it’s hard to tell apart similar consonants like /m/ and /n/. That, in turn, makes words hard to understand).

- Why can I remember some facts so well and others so poorly? (I remember what relates to my interests, what has meaning, and what can be set to music. I can’t remember what I try to memorize by rote).

- How can I write grammatically while unable to remember what a dangling participle is or why it’s incorrect?

- How can I memorize concertos and develop perfect pitch, while making no sense of music theory?

- Why can I dance gracefully to music, while in dance class, I miss steps and am constantly on the wrong foot. (I’m still not sure about this one).

Neurodiverse writers were asking themselves similar questions and finding interesting answers.

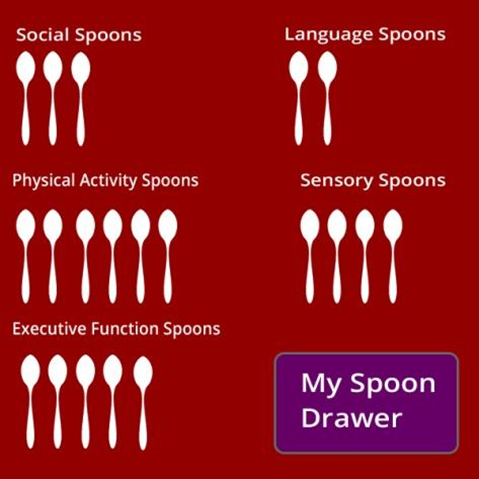

Cynthia Kim’s “Conserving Spoons” is a great example. (Here, following Christine Miserando’s metaphor, the word “spoons” refers to limited energy reserves that do not quickly replenish). Cynthia Kim realizes her energy reserves vary, with much more energy for physical activity and executive functioning than socializing or language. Realizing this, she can make more informed choices about how she spends her energy: “I can…conclude that an hour-long run in the morning isn’t going to impair my ability to work afterward. An hour-long meeting first thing in the morning will.”

She also asks herself, “if the cost is high, what kinds of discounts (accommodations) might bring the sticker price down into a range that you can afford?” Small changes in how she does everyday tasks can make a difference. “I know that a social activity will cost more…if I have to wear uncomfortable clothing or can’t take a break when I need to. A similar activity may have a lower…cost if I attend with someone who can run interference for me.”

My own distribution of “spoons” is very different from hers. Yet, when I agonized over how to divide too little mental energy between too many tasks, strategies like these helped me come up with solutions.

I found words for my experiences

Years ago, an anonymous person commented on my personal blog, saying something like, “you mean there are words for this?!”

I know the feeling.

I watched as neurodiverse people invented language to talk about our experiences. Words like these:

- Sensory overload: an uncomfortable experience that happens when people are bombarded with too much sensory information for longer than they can handle. People describe what it feels like at The Mighty.

- Hyperfocus: A state of concentration so intense that people lose awareness of the passage of time, events happening around them, and sensations in their bodies. It can lead to working for hours and then suddenly “coming,” exhausted, hungry, and thirsty, as shown in this meme. Neurodivergent people may be especially prone to hyperfocus because our attention is all-or-nothing, like an on-off switch instead of a dimmer switch.

- Hyperfixation: A non-insulting term for the extremely focused, passionate interests in specific topics neurodivergent people often have. One trend on neurodivergent Tumblr is to put boxes on their profiles that say “this user has a hyper fixation on x.” Aure explains how hyperfixations create an order for our brains that motivates us and connects us to the tasks we have to do.

- Brain fog: a mental state that involves fatigue and difficulty paying attention, thinking, and remembering. It plagues not only neurodivergent people but also people with all sorts of physical and mental illnesses. I describe what it feels like here.

- Autistic burnout: As Judy Endow explains it, autistic burnout is when “we come to the end of our resources that enable us to act as if we are not autistic in order to meet the demands of the world around us.” Since 2011, people on Wrong Planet have been describing their experiences with autistic burnout here.

- Inertia: Kristin Lindsmith describes it as “the autistic difficulty with starting new tasks (mental or physical), as well as stopping already started tasks. Sometimes described as a difficulty with figuratively ‘changing gears.’ A combination of attention shifting and motor planning difficulties. Unrelated to motivation, desire, or choice (i.e., wanting to do something doesn’t necessarily make it easier).” Several autistic people explain what autistic inertia feels like on Quora.

It’s easier to understand yourself, explain yourself to others, and ask for what you need when you don’t have to invent the language for doing so.

I was accepted, warts and all

The first time I went to an in-person meetup for people with ADHD, it felt like a weight had been lifted from me. Despite being in a group of strangers, I felt relieved and safe.

One reason was that, for the first time, people around me talked the way I did. Usually, I feel off-rhythm, like everyone else is waltzing while I’m doing the tango.

I tend to “ramble.” I start out saying one thing, go into an example or explanation, go off on a tangent, and if I’m lucky, finally return to the main point much later.

I also tend to get excited and interject support or agreement. This is called “conversational overlapping,” and is common among New Yorkers and some Mediterranean and South Asian cultures. It signals enthusiasm and interest but can be misinterpreted as a rude interruption. Many people I’ve met in ADHD groups, especially women, talk in this way.

After the meeting, several of us hung out for almost an hour in the hallway, chatting. It felt like I’d found long-lost relatives.

Another reason I felt safe was I wasn’t afraid people would see “the awful truth” about me and reject me.

If I was a few minutes late to the group, well, some of us were up to half an hour late.

If I accidentally interrupted someone, I wasn’t the only one. I apologized and we all forgot about it and moved on.

If I misheard or misunderstood someone, I could ask what they said without worrying I’d be judged for asking a “stupid question.”

It was liberating.

Normally, when in groups, I constantly worry whether I look and sound “appropriate.” It’s exhausting, and sometimes, it’s easier not to talk at all.

In neurodiverse groups like these, I can drop the mask.

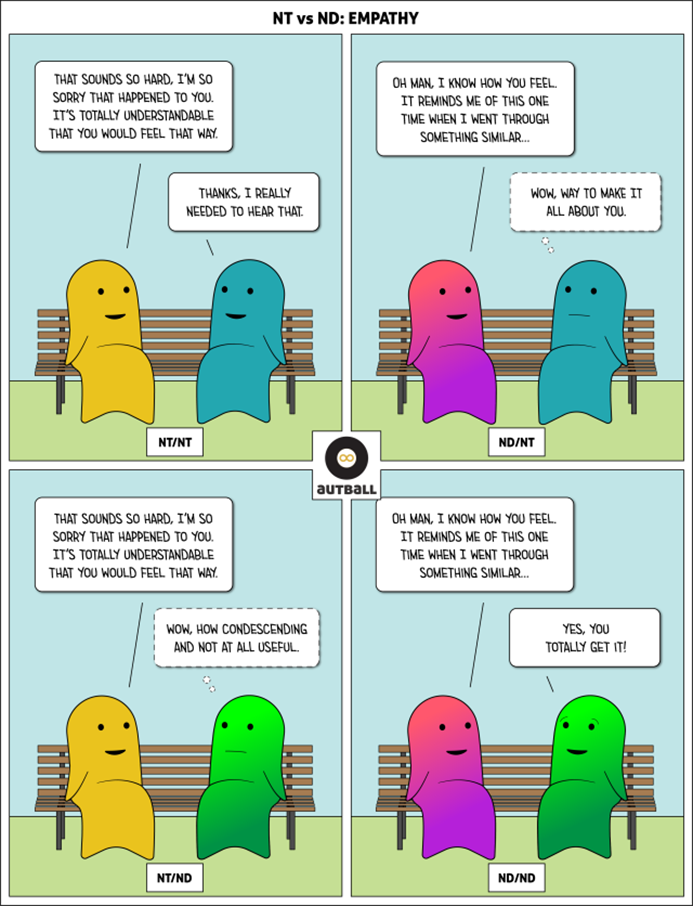

People get it, so they can commiserate

Here’s what happens when you get a group of neurodiverse people together. (Doesn’t matter if they’re in a Twitter chat, on Discord, on Tumblr, or in person).

Somebody talks about an experience. They might say, “I’m depressed today and I’m having trouble getting things done.” Maybe they tell a story showing what that looks like. Somebody else says, “Me too! Here’s what’s going on with me…”

Pretty soon, you have a chain of stories.

It’s a kind of empathy. People aren’t just saying, “Oh, that’s too bad” or “I know how you feel” when they actually don’t. By sharing their experiences, they’re proving they really get it.

It’s encouraging. It’s validating. It’s connecting. It’s comforting.

It’s not all doom and gloom, either. Sometimes, we tell jokes. That’s especially helpful on days when it feels like my brain hates me and is trying to sabotage me.

Nothing says “bonding” like joking about the annoying things our brains do.

People get it..so they can give better advice

Allie Brosh, the author of the Hyperbole and a Half blog, describes the terrible advice well-meaning people gave her while she lived with depression. “It would be like having a bunch of dead fish, but no one around you will acknowledge that the fish are dead. Instead, they help you look for the fish or try to help you figure out why they disappeared.” In frustration, she wanted to reply, “no, see, that solution is for a different problem than the one I have.”

It was like a never-ending parade of that person we all joke about whose answer to every problem in life is, “have you tried doing yoga?”

I’m sure Allie’s friends and family loved her and wanted to help. They simply hadn’t experienced what she was going through and didn’t know what they didn’t know. They would have done better to keep the advice to themselves and find other ways to help.

A loved one tells me I could better keep track of my belongings and remember appointments if I followed a routine consistently. He’s right. However, the advice doesn’t help, because I also have difficulty doing anything consistently.

Ironically, I struggle to maintain a routine for the same reasons I need one in the first place.

I talk with other people who have difficulty keeping routines. Occasionally, they’ll mention something that’s helped them. It’s always worth considering and trying. Sometimes, the suggestion will never have occurred to me before.

The best advice I’ve encountered has been from other neurodivergent people.

I didn't have to explain everything

I have a bad habit of overexplaining why I say and do things. At best, it’s too much information. At worst, it sounds like excuse.

When I was a child, I hated when people asked, “why would you say/do that?!” while staring at me like I’d grown another head. It hurt. However unreasonable my behavior may have seemed to them, I did things for reasons that made sense to me. All people do.

Now, I launch into an explanation of my motives before anyone even asks.

I constantly feel the need to explain myself. Most of the time, when I interact with people, I’m painfully aware that:

- Most people’s “normal” and “enjoyable” experiences are uncomfortable, tiring, or overwhelming for me. I love to dance, but not at a crowded dance club with near-deafening music. I enjoy food and people-watching but avoid the Taste of Chicago.

- What’s easy for most people is hard for me, and vice versa. I love reading but struggle to focus on and understand YouTube videos. I did better in upper-level college classes (where you learn in-depth and write essays) than in intro classes (where you skim a lot of content superficially and do multiple-choice exams). It was easier for me to do neuroscience research than work as a barista.

- It’s hard for me to converse about common topics, such as actors or places people have been to. I struggle to understand movies, recognize actors, learn my way around new places, or remember which restaurant had that pho I like.

- Many people don’t enjoy thinking in the ways I do. My friend doesn’t want to ponder why her boyfriend did that strange obnoxious thing, she just wants me to agree that he’s awful and sympathize with her.

Many people also don’t seem to carry around the same fears and expectations I share with many neurodiverse people:

- The expectation that I will be different everywhere I go, and the fear that I will not belong.

- The belief that people will think I’m weird if I show my real thoughts, feelings, likes, and dislikes. The fear that people will reject me if they see “what I’m really like.”

- The belief that all awkward or unpleasant interactions with people are my fault, and it’s my responsibility to make every conversation go smoothly.

- The fear of admitting I don’t know something or asking for help.

- The belief that I have to impress everyone with my strengths so that they will forgive my weaknesses.

It’s like going through the world knowing I’m wearing lenses that turn everything blue while most people are wearing lenses tinted red. Much of what I do will be lost in translation. However, I can’t always predict in advance what I will need to explain. So I’m hypervigilant and err on the side of explaining everything.

It’s exhausting.

When I interact with other neurodivergent people, I know they’re more likely to be wearing blue lenses, or at least purple ones. Plus, we’re used to having to explain ourselves and worrying about being judged. So, we’re often less judgmental . At the very least, I’m less likely to be given that look that says, “what’s wrong with you?”

It’s an immense relief not to have to explain every darn thing all the time.

I found a sense of purpose

A few weeks ago, a good friend told me a blog post I’d written helped her understand her girlfriend, and now they get along better. This was one of the proudest moments of my life.

Another golden moment was when a reader, who suspected they had ADHD, said I’d encouraged them to pursue a diagnostic evaluation.

I participate in neurodiverse communities because I want to help them do for the next generation what they have done for me.

I want younger neurodivergent people to have easier, more connected lives. I want them to grow up feeling like they belong and knowing people like themselves. I want them to be surrounded by people who can help them figure out how their brains work. I want them to be able to be themselves and still make friends, have relationships, and work. I want them to have opportunities to develop their talents and use them to improve the world.

In short, I want them to have what many people take for granted, and everyone should experience it.

TL;DR

Participating in neurodiverse communities transformed my life.

- It helped me realize I wasn’t the only person who experienced life the way I did.

- It helped me understand myself.

- It gave me words to explain myself to others.

- It introduced me to people who accepted me the way I was.

- It gave me a place where people could commiserate and offer relevant advice.

- It gave me a place where I didn’t have to explain everything.

- It gave me a sense of purpose and ways to help others.

Being diagnosed late meant a piece of myself was hidden. Other neurodivergent people helped me find it.

If you’re reading this, you might have a similar story. Maybe you were diagnosed late, too. Or, maybe you’ve never been diagnosed with anything, but you grew up feeling different and wondering why life was so hard. Or, maybe a loved one experienced something like this. I invite you to reach out. Ask questions, or tell your story. You might just meet people who see and accept you for who you are.

What about you?

Have you, or a neurodivergent loved one, interacted with any neurodiverse communities? What was the experience like? If you were diagnosed late or not at all, did they help you look at your life differently? If you were diagnosed as a child, what is participating in a neurodiverse community like for you?

[1] I use the word “neurodiverse” for groups, and “neurodivergent” for an individual person. A “neurodivergent” person’s brain learns and develops differently than the majority. Often, that comes to people’s attention because of difficulty doing something (like reading or making friends), which can lead to getting a diagnosis (such as dyslexia or autism). A “neurodiverse” group is one with many kinds of minds in it because it includes neurodivergent people. The neurodiverse communities I’m talking about here are ones set up by and for people with various neurodivergence, as well as their loved ones.

Emily Morson

About the Author

Emily M. is a writer fascinated by the infinite variety of human minds. She grew up inexplicably different and was diagnosed as an adult with several forms of neurodivergence, including ADHD and an auditory discrimination disability. Feeling as if she were living life without a user's manual, she set out to create her own. In the process, she met other neurodivergent people on similar quests. She began working with them, advocating for inclusion, accessibility, and autism acceptance. Seeking to understand how neurodiverse minds work, she became a cognitive neuroscience researcher.

Her favorite research topic: what do children learn from their intense, passionate interests? Wanting to help neurodivergent people more directly, she trained as a speech/language therapist. Ultimately, she turned to writing, combining research with personal experience to explain autism and ADHD and champion acceptance – because everyone is happier when they are seen and accepted for who they are. She envisions a world where neurodiverse people have equal opportunities for education, loving relationships, and meaningful work.She also blogs about autism and ADHD research at Mosaic of Minds. You can chat with her on Twitter: @mosaicofminds.